In 2019—the same year he won the US National Road Race Championship—Alex Howes rolled up to the start line of Dirty Kanza. Ahead lay 200 miles of farm tracks and flint hills in a gravel race now known as Unbound. Riding with friend and teammate Lachlan Morton in the colours of Education First, their race was documented in what would become a series of inspirational films capturing the highs and lows of this alternative racing calendar.

Recently retired from the World Tour but still working with Team Education First as a cycling coach, Alex is now forging a new career as a gravel racer—a professional pivot that he discusses over a transatlantic call from his home in Nederland, Colorado.

A freewheeling and candid conversation that takes in everything from family road trips to bears, bugs and beards, Alex turns the page from World Tour to Tour Divide and what it takes to ride 2,963 offroad miles in a little over 19 days.

cyclespeak

Hey, Alex. How’s it going?

Alex

It’s going alright. Yourself?

cyclespeak

Good, thanks. It’s breakfast time on your side of the world and I can see you’ve already got a coffee on the go.

Alex

We had a huge storm last night so we were up a fair bit. Right on top of us—I couldn’t believe how loud it was. I’m not usually afraid of lightning but that was something else.

cyclespeak

In the media we’ve seen some pretty extreme weather over in the States. Or are these storms the norm for you at this time of year?

Alex

It can happen, for sure. A lot of people living up here have double surge protectors on their houses. And we occasionally get this dry, static air that makes for some super intense lightning.

cyclespeak

How remote are you? Where’s your nearest store if you want a pint of milk?

Alex

We’re not way out there but that’s kind of by design. When I was racing in the World Tour I needed to be able to get to Europe relatively quickly. So we’re 30 minutes up the canyon from Boulder in a little town called Nederland. There’s a local store where you can pretty much buy everything you need. And I can be out the door here and over to Frankfurt in 12 hours.

cyclespeak

I saw a lovely post of you and your little girl at a local cycling event. May I ask how you’ve taken to fatherhood? From my own experience, it’s rather a rollercoaster ride.

Alex

I think that’s the right way to describe it [laughs]. And I was not so long ago thinking how bike racing and fatherhood are one and the same. Birds of a similar feather.

cyclespeak

I can’t resist asking you to elaborate on that.

Alex

You have these moments of extreme joy when you wouldn’t swap it for anything in the world. And then you get moments where you’re like, what have I done [laughs].

cyclespeak

I don’t think anyone is quite prepared for it. And maybe if we did understand how challenging it can be, we’d think again. But then you have people wanting to do it all over again. I remember my wife saying to me that she wanted another baby and I’m thinking really.

Alex

That’s where we’re at now. We’ve got this pretty good kid who’s also a big handful.

cyclespeak

If it’s any help, I’ve got two boys and from experience it isn’t like having one plus one. It’s more like one and two thirds because a lot of the decisions you faced the first time around you’ve already made. So I probably enjoyed the process more with our second child which I guess sounds a little strange.

Alex

But you survived and they’re society’s problem now [smiles].

cyclespeak

Not as a strict rule but children do tend to flourish with a sense of routine. Does that sit well with you or do you prefer things to be a little more haphazard?

Alex

I don’t know if it’s a preference but I guess that haphazard best describes how I’ve lived my life for the last 35 years. But I do agree with the idea of routine and we definitely pay for it when our daughter goes to bed late. And this year we’ve been cruising around in a travel trailer to a bunch of races.

cyclespeak

Say you’ve got a race weekend and it’s just you. How does that compare to when the family is travelling with you? I’m guessing it’s a very different experience?

Alex

The solo mission is definitely lower stress [laughs].

cyclespeak

You can focus solely on you and your race?

Alex

With the little one, dinner’s at 6:30 whether or not you need to be doing something else. And if we don’t keep to that schedule we’re screwed for the next day.

cyclespeak

Consequences [smiles].

Alex

There’s a little give and take but it’s also been fun and we’ve visited some really cool places as a family.

cyclespeak

We’ve already mentioned that you live in Colorado and I was watching your Fat Pursuit* series of Instagram stories where every film clip shows longer and longer icicles hanging from your beard. And I was wondering whether you relish difficult ride and race conditions or does the professional in you just get the job done?

[*a winter race ridden on fat bikes]

Alex

I actually didn’t view the Fat Pursuit as particularly difficult…

cyclespeak

You didn’t [laughs]…

Alex

The event itself was hard but I had the right equipment. And with the conditions, they are what they are. It’s a dry cold which is very different to your winters in the UK where you’re just soaked to the bone.

cyclespeak

Tell me about it [laughs].

Alex

I couldn’t do that. Well, I could because the professional in me would just get on with it but would I want to? Whereas over here, the wind can kick your butt but the snow stays snow for the most part and you just need to manage your layers. Other than that, the only thing that’s cold is your nose [laughs].

cyclespeak

You enjoyed a ten year World Tour career riding at the pinnacle of professional road cycling. A little bit of a clichéd question but is there anything about that lifestyle that you miss?

Alex

Honestly, it’s the team aspect that I miss the most. I’m now having a lot of fun, doing my own thing, but at the same time that camaraderie between the riders and support staff— all working towards a common goal—it’s cool. It was fun sitting on the bus, knowing exactly what you’re doing that day. High pressure but with high reward.

cyclespeak

And now?

Alex

If I wake up and don’t want to do something, I generally don’t do it [smiles].

cyclespeak

Looking at the age of the GC riders now winning Grand Tours, in your opinion are long, established World Tour careers a thing of the past?

Alex

That’s a good question. The races are definitely more intense—a lot more explosive. Everyone’s going faster and in order to make that happen that’s reflected in the amount of dedication required in the riders. It’s always been said that cycling at this level is a 24/7, 365 type of job. And I look at how hard some of these young men and women are training and it’s pretty incredible. So maybe you will see shorter careers but I’m not sure whether that’s necessarily a bad thing. There’s a lot of living left to do after you finish racing.

cyclespeak

I can remember hearing the results of the 2019 National Road Race Championships when you finally got that jersey after a number of attempts. I’m guessing the feeling as you crossed the line was one of euphoria but was there also a sense of writing your name in the cycling history books? An achievement no one can ever take away from you?

Alex

It was pretty special but I think I’d already realised that it almost doesn’t matter what you do in cycling. It’s very fleeting. You take Jonas Vingegaard as an example. He wins this year’s Tour de France and for a few days his name and face are featured on every media platform but the focus soon shifts to who will do well at the Vuelta. And that clock doesn’t stop and there’s a new champion every year. And whilst it’s fun and special to have your name on that list—in years to come you can scroll back and say, yep, I’m still there—it’s not a bronze statue in the centre of town.

cyclespeak

So what was the motivation as you rolled up at the start line?

Alex

The big shift was being diagnosed with hyperthyroidism in 2018 and the subsequent concern that my racing career was over. And then coming back hard in 2019 with the feeling that anything I achieved was for me. Not for the headlines, not for the history books. And, looking back, I think that shift in mentality was a major contributing factor to winning that year.

cyclespeak

It sounds to me like there was less pressure?

Alex

Going into it, I was on the radar but I don’t think anybody had me down as the favourite. At that point, people weren’t sure whether I was still a bike racer.

cyclespeak

But you took the win and in the subsequent couple of years combined a road programme with gravel and mountain biking. And I was chatting with Pete Stetina and he was contrasting his World Tour days when he had a team to do everything for him and now he’s putting in super long weeks organising everything that goes with being a gravel privateer. So I was wondering whether you’ve also seen this shift?

Alex

It’s interesting because I will admit that organisation and routine are not my particular strengths. And now that everything comes down to me—for better or worse—what that looks like is I’ll do an event like the Tour Divide, have a great time but only reply to a handful of emails in a month. Then I get back home—totally shattered—but need to put in 80 hour weeks getting my life back on track. So it comes in big waves and surges with fatherhood and training also needing to fit into the equation.

cyclespeak

You’ve got it coming at you from every direction.

Alex

I’d be lying if I said I always keep track of it all. So I just try and do my best [laughs].

cyclespeak

I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve watched you and Lachlan [Morton] in the Dirty Kanza and Leadville films for Rapha. Was there a sense that you were a crucial part of something really special in cycling?

Alex

That whole time with EF Gone Racing was fun. I know it was something Lachlan always wanted to do and we were both sort of dabbling in it anyways. We both genuinely love to race and there’s a big difference in the emotional and physical toll of a race like Leadville that’s literally on my doorstep, two hours from home. Especially when the alternative is getting on a plane and flying to Europe to spend three months cranking out a bunch of World Tour races. To be able to do a backyard brawl, that’s good fun for us.

cyclespeak

And then they decided to make the films?

Alex

It was a pretty unique situation to have both EF and Rapha talking about off-road racing. And we’re like, yeah, we’re already doing that. Bring your camera [smiles].

cyclespeak

And the films proved a huge success.

Alex

It quickly became apparent the impact it was having. The number of times that people have come up to both of us and said it was the reason they’d started riding a bike. I remember I had one guy who told me he’d lost 70 lbs after watching those films and was going to ride the 200 at Unbound.

cyclespeak

How does that make you feel? When people tell you they’re now healthier and happier because they watched a bunch of films featuring you and Lachlan riding your bikes on dirt?

Alex

On the one hand it’s special—super cool—because the more people on bikes the better in my opinion. And I’ve personally seen it change so many people for the better. They calm down and slim up [laughs].

cyclespeak

I sense there’s a but?

Alex

Myself and Lachlan, we’re not anything particularly special and sometimes it feels like people put us on a pedestal or look to us for answers. And I’m just a dude on a bike too. They just happened to bring a camera along.

cyclespeak

Personally I think there’s a lot more to it than that and there’s obviously something really special in these films that connects with people. But let’s fast forward a few years and look at how gravel racing seems to be going through some growing pains—kind of difficult teenage years—as it transitions from a no rules, race-what-you-brung sport to the ongoing concerns over winning at all cost and team tactics. As you come over as never taking things too seriously, do these issues have any impact on the way you race?

Alex

I get frustrated because most of these issues are just details that may or may not need addressing. And if you want to deal with it as a rider, just say something during the race.

cyclespeak

Is that something you’ve done?

Alex [pausing as he gathers his thoughts]

I can get pretty heated in a race situation. I still have that in me. In my mind, that’s what the race is for. That’s our arena. That’s where you do it. You can say whatever you want during the race—get properly wound up—and then you cross the finish line. I don’t understand why people throw stuff up on social media or start screaming at each other in the parking lot. The race is over. Let’s put all that away and get on with our lives.

cyclespeak

How does this all compare to the years you spent road racing?

Alex

In the World Tour, it’s probably a lot more common than people realise. It’s super dangerous, riders are taking big risks, you have a director in your ear telling you to get this or that team out of the way. It’s messy out there but then you get done, get out of your race kit and life goes on.

cyclespeak

You scored a top ten finish in last year’s Lifetime Grand Prix series. Was that a race format that suited your riding style? Did you enjoy it?

Alex

I do like the Grand Prix. I think it casts a spotlight on off-road racing and that’s a net positive for the sport. But does it suit me? Not necessarily [laughs].

cyclespeak

Because it’s both mountain biking and gravel?

Alex

It’s two disciplines but I think it’s the style of racing that isn’t the best fit for me. I was always more of a punchier rider—hitting really high short power numbers repeatedly throughout a day—whereas gravel and mountain biking are a bit more diesel if that makes any sense? Hard on the pedals without ever going too hard. The average power is high but the spikes are low. But that doesn’t mean I don’t try [smiles].

cyclespeak

And you’ve just recently got off the Tour Divide. A big daddy of an ultra distance event. You prepped the ride with a fully sussed Cannondale Topstone but I was wondering how you work on your head game for such an epic undertaking?

Alex

Honestly, I’m very fortunate that I have 20 plus years riding bikes under my belt.

cyclespeak

And you have ridden all three Grand Tours.

Alex

I guess you could say I’ve been around the block a couple of times [smiles].

cyclespeak

So mentally, you were dialled in?

Alex

The hard part about Divide—but also the nice thing—is that it’s basically an individual event. So you never have to go any harder than you can. Whereas with World Tour racing—this will sound silly because you can’t give 110%—but the number of times in any given race that you’re absolutely on your limit but you somehow have to figure out how to continue just so you can hold a wheel. And sometimes you can’t figure it out and you get dropped and you’re out the back and you have to sell your soul to make the time cutoff.

cyclespeak

And riding the Tour Divide?

Alex

You might mess up but you can always decide to call it for the day and climb into your sleeping bag. You get to make those choices [laughs].

cyclespeak

I was slightly concerned because you were clean shaven at the start. Was that at the risk of removing your bearded super powers?

Alex

I figured I’d be scruffy enough by the end [laughs]. And in hindsight, I do wish I’d left a bit of beard on there because of the bugs. Every time I had a mechanical—which happened a few times—I was just swarmed. I lost a lot of blood to mosquitoes, let’s put it that way.

cyclespeak

Inspired by your Tour Divide video diaries, I’ve gleaned a few topics of conversation. The first being bears and other animal activity. Any close calls?

Alex

Luckily none for me but some people saw a number of bears.

cyclespeak

Lael Wilcox encountered a mountain lion during a past Tour Divide attempt.

Alex

Mountain lions are certainly a feature of that neck of the woods. But it’s the grizzlies up north that scare me [laughs].

cyclespeak

You also had some problems with your wheels? [Alex fashioned a replacement wheel spoke from a piece of rope]

Alex

That was unfortunate. I thought I’d done my homework but I think I’d underestimated how much weight I was carrying. And then you’re tired and smashing into stuff in the dark. So making spokes out of rope was definitely a first for me. It took some thinking to get that done.

cyclespeak

It looked like a fascinating fix.

Alex

It’s a good example of what you can figure out when you have time and no other options. I was pretty shit out of luck so just took everything I had and spread it out on the ground.

cyclespeak

Kitwise, you seemed pretty impressed with your Velocio raincoat?

Alex

Oh man. That thing’s insane. It was so good having that big pocket on the front so I could fully kangaroo stuff. I’d even told Ted King—we’re both sponsored by Velocio—that he should get one. With the hood, you can get fully sealed up in there and he messaged me after I’d finished to let me know that he was equally impressed with how it performed.

cyclespeak

The weather wasn’t kind?

Alex

Some years it’s off-on with the rain but this time, that first week was grim.

cyclespeak

It did look pretty gnarly—wet and windy.

Alex

The only complaint about that jacket was the side zip. For whatever reason I’d lost a bunch of strength in my left hand. It’s slowly coming back—don’t worry, I’m seeing somebody [laughs]—but it was difficult to work that zip. So user error rather than any fault in the jacket.

cyclespeak

What was your record for the number of coffees in a single day?

Alex

Funnily enough Divide was a bit of a detox in terms of caffeine. A lot of that is just logistical. You’re way out there with only so many places you can get one. Some riders like to carry one of those canned coffees which they’ll drink at 9:00pm before riding into the night. I’d drink it first thing in the morning to try and maintain some sanity.

cyclespeak

Do you lose weight riding a race like the Tour Divide?

Alex

I think I’m the only person that didn’t [laughs].

cyclespeak

Really?

Alex

I’ve got a pretty strong stomach. Probably a good thing because my general plan was to just eat everything. So my weight didn’t change but maybe my body composition did? I gained a little in my upper body from muscling around a 50 lb bike.

cyclespeak

Is there any public bathroom etiquette for washing, sleeping, shelter?

Alex

After the first couple of days, people are pretty spread out. But saying that, the toilets are kind of a hot commodity. One reason being they’re free, there’s a nice flat surface to sleep on and minimal bugs inside. And up in grizzly country you can lock the door. But honestly, I was trying to get a hotel whenever it made sense. So it probably broke down to roughly 50:50.

cyclespeak

The benefits of a hot shower and a bed to sleep in?

Alex

I wasn’t consciously thinking of hygiene as a performance boost but you soon come to the realisation that if you don’t take care of yourself, you can’t sit down [laughs]. My butt hurt way more if I slept in a bivvy bag and especially during that first week when everything was soaking wet.

cyclespeak

Was staying dry an almost impossible task?

Alex

I’d packed two pairs of bib shorts but they’d both be wet. So you just need somewhere to get properly dry. And a hotel is really the only option.

cyclespeak

That makes sense.

Alex

Not that it’s a plan that always works out. Because my bibs had those utility pockets on each side and what I’d forgotten was the foil wrapper that I’d stuffed inside. So I was in a hotel and decided to dry them out in a microwave.

cyclespeak

What could possibly go wrong [laughs]?

Alex

Well, they caught fire and I burnt a hole in the bibs. Which really bummed me out because they had the most amazing chamois. But anyways, I still wore them for the rest of the race.

cyclespeak

In terms of other equipment, did you take the right bike?

Alex

Definitely the right bike but there were a few times when slightly bigger tyres would have helped.

cyclespeak

What size were you running?

Alex

45 mm and pretty rugged. They rolled nice and quick on the faster stuff. So it was only when the surface got a little broken up that I wanted anything wider.

cyclespeak

You rode flared gravel bars?

Alex

There was no way I could ride the Divide with a flat bar.

cyclespeak

Not enough hand positions?

Alex

It breaks up the day when you can switch between the hoods and the drops.

cyclespeak

Which I guess is important as you rode 2692.9 challenging miles over 19 days, 14 hours and 46 minutes. What were your emotions on completing this awesome achievement?

Alex

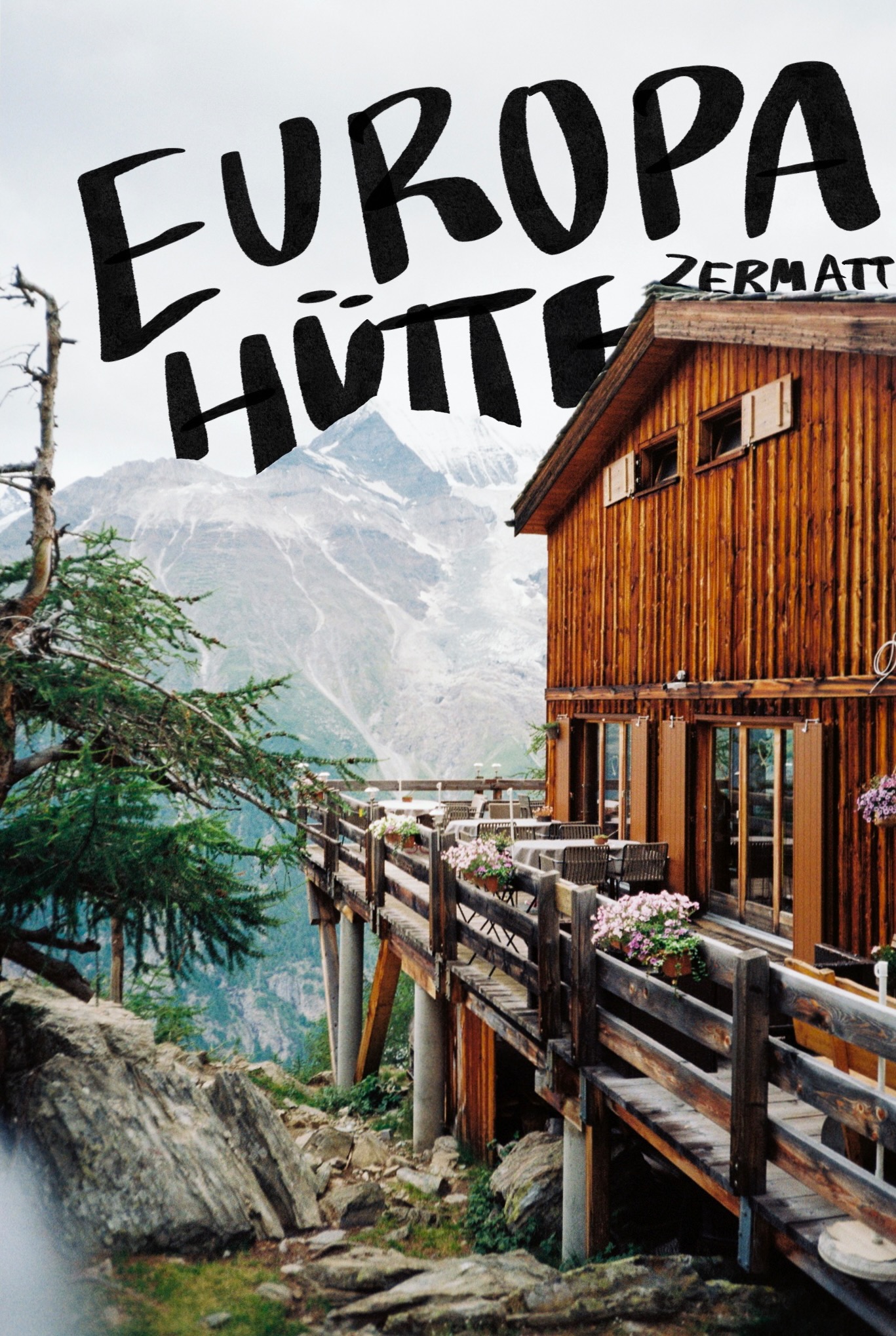

The finish for Divide is kind of anticlimactic—just a wire mesh fence on the Mexico border. But I got lucky because an old friend and his wife have a house down in Silver City and it just so happened that they were staying there at that time. So he picked me up and gave me some clean clothes. The alternative is you arrive in Antelope Wells, on your own, most probably in the middle of the night. It’s definitely not like finishing the Tour de France on the Champs-Élysées.

cyclespeak

Now you’ve had time to process your experience racing the Tour Divide, is it something you can see yourself doing again?

Alex

Honestly, I don’t know. Firstly I’ve got to see how this left hand comes back. I’m kind of attached to it and the Tour Divide doesn’t mean enough to me to risk permanent damage.

cyclespeak

And you completed it, so it’s not exactly unfinished business.

Alex

And I’m so happy that I decided to ride it. Most people that attempt it, for whatever reason they have this idea of finishing in 20 days. And if you think about it, that’s like trying to ride Lachlan’s Alt Tour in the same amount of time…

cyclespeak

But on way more challenging surfaces and with the possibility of bumping into a grizzly bear [smiles]…

Alex

And there’s also the sleep aspect. I kept relatively well rested and I’m fortunate to have this off switch that certainly helps. When our little one was born, we pulled an all-nighter and then the next night only got three hours of sleep because we were still in the hospital. So when we got home, the baby’s right there in the bassinet and my poor wife is up and down all night feeding her. And me—no eye mask or ear plugs—I’m dead to the world.

cyclespeak

Have you any idea how irritating that is for the person that’s up [laughs]?

Alex

I thought she was going to kill me.

cyclespeak

Even so, that’s a pretty special skill. And useful on ultra-distance events?

Alex

It is. Assuming you don’t sleep through your alarms like I was doing on Divide [laughs].

cyclespeak

So what gets you up and out of bed with a spring in your step now that Tour Divide is done and dusted?

Alex

Right now, I’m having fun getting back to racing. Divide was—not so much a vacation—but a bit of a detour. I wanted to do it, I did it and I had fun with it. Now it’s a case of seeing whether it broke the motor. Maybe I’m more diesel now? So to answer that question, I’ll be cruising around with the family to a bunch of gravel races I’ve got lined up to finish out the season. With a three year old in tow [laughs]. That’s not scary at all, right?

Thanks to Alex Howes

Feature photography by Chris Milliman with kind permission of Velocio

Second ‘family album’ image by Gretchen Powers