High on a hillside with a view towards the sea, sits the cabin belonging to Henna Palosaari and her partner Adam Gairns. Now entering their second year of ownership, Henna unpicks the joys—and some of the challenges—that come hand-in-hand with renovating a remote, off-grid property: their future plans, an acknowledged need for patience, and how they’re sifting the puzzle pieces of a simpler way of living.

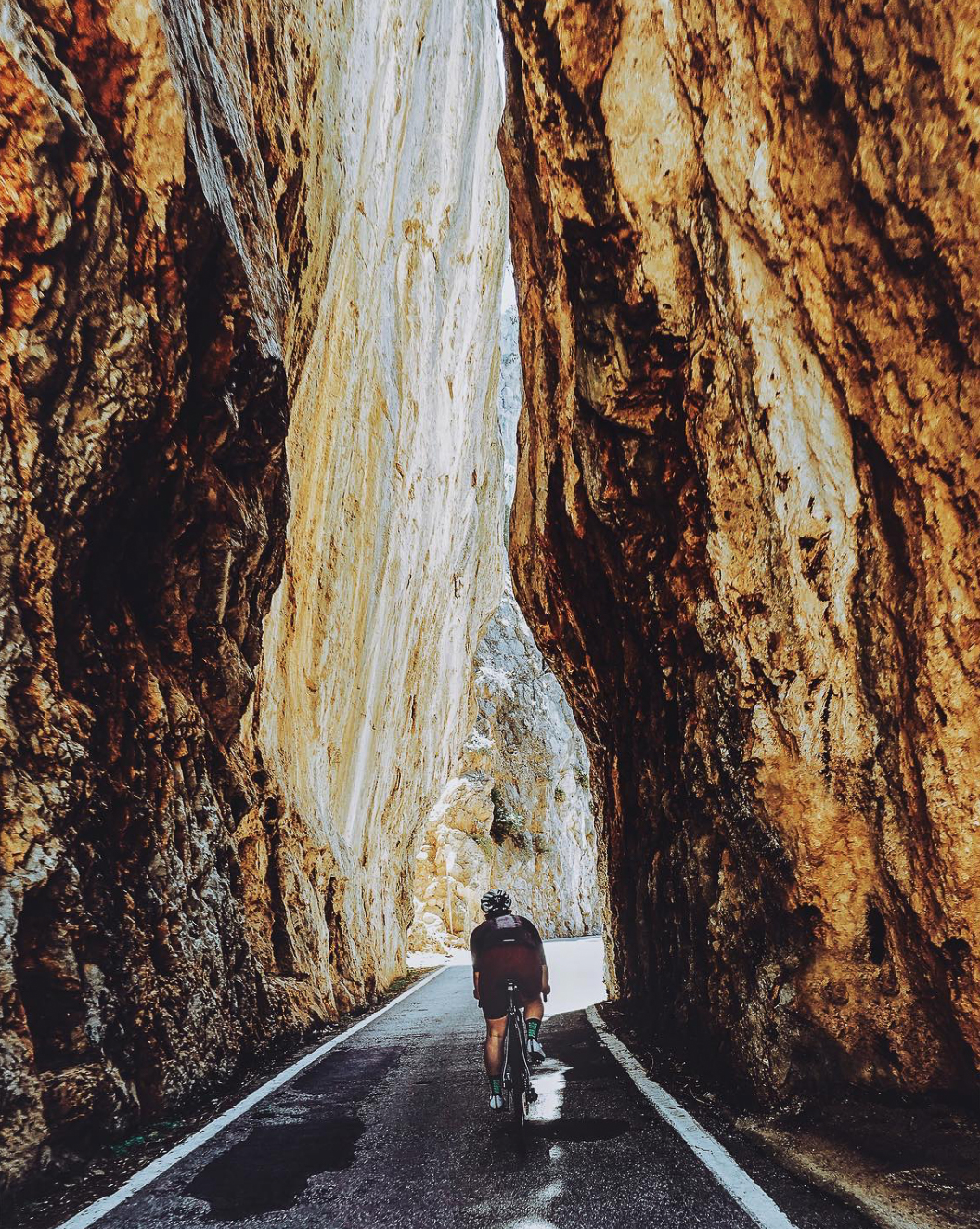

The last time we sat down to chat—almost two years to the day—Henna had finished up renovating her classic Mercedes camper van Eldo. Not perhaps the swiftest way to travel, Henna points out, as she regales me with the trip she took late last year with Adam all the way from Norway to the north coast of Spain.

“Luckily we were able to stay for two whole months before heading back home—surfing, riding our bikes, just slowing everything down—which was perfect.”

Not afraid of getting her hands dirty and clearly competent—Eldo did make it all the way to Spain and back—what followed was a series of posts and stories on Henna’s Instagram feed that documented the first stages of another renovation project; the pair having purchased a remote cabin a few kilometres inland from the hamlet of Hoddevik on the west coast of Norway. Which I admit to Henna has me a little puzzled, as she lives in Finland?

“I grew up in Oulu—a city in the north of Finland—and then lived a rather nomadic life before moving to southern Norway just shy of two years ago. But I really like going back home every now and then to visit my parents at their cabin in Lapland where we can Nordic ski.”

So there’s the cabin connection, which prompts me to ask what first inspired Henna and Adam to start searching for a property by the sea and whether they had a shopping list of certain features?

“It’s rather a funny story,” explains Henna, “because it was more a case of the opportunity being dropped in front of us followed by the realisation that we had to grab it with both hands. And it all started when friends of friends were visiting Hoddevik to go surfing. One evening an elderly couple walked into the hostel where they were staying and asked if anyone wanted to buy a cabin. They explained how a recent storm had swelled the stream that cut across the path from the road to their cabin to such an extent that the couple were unable to reach their property. Tired and a little fed-up with the remoteness of their summer home, they’d decided—right there on the spot—to sell up and find something a little more convenient. Our friends’ friends live in Sweden so it was too much of a logistical challenge but they mentioned it to our mutual friends and they, in turn, told us. And because the elderly couple were so desperate to get rid of the cabin, very fortunately Adam and I were able to make a deal before it was even on the market. Because it’s doubtful we would have been able to afford the purchase price if there were other interested parties.”

Through the seasons

Click an image to open gallery

Clearly a serendipitous series of coincidences but I’m curious whether it was always going to be a yes? Or was there ever a moment when Henna and Adam considered passing?

“It came so out of the blue that we hadn’t even talked about it. But when we did discuss the practicalities—how we could use the space moving forward—it slowly started to make perfect sense. At the moment, if we want to surf, we have to travel three and a half hours which means taking Eldo. If we have a cabin by the sea, it will be so much easier to keep our surfing things ready and waiting. And the scenery in Hoddevik is stunning and reminds Adam of Scotland where he grew up.”

Taking a moment to gently tease Henna for the broad Scottish accent she adopts when mentioning the country of Adam’s birth, I then learn how—rather than agreeing a deal sight unseen—they twice visited before finally committing.

“It’s not in any shape or form a fancy cabin—it was immediately clear how much work will be needed—but we liked it immediately. And you have to hike a little bit to reach the cabin from the road, which in turn means that we have to carry everything from where the car is parked. But the big windows let in so much light and there’s a tree in the garden that frames the view to the sea.”

Placing the cabin in the landscape for me, Henna describes how you park on the side of the road that leads to Hoddevik. From there it’s a short section of double track to allow access by tractor to the cows and sheep that graze the hillside in the summer. This then narrows to a footpath which crosses a stream that you hop over from one side to the other.

“That’s if it hasn’t rained heavily,” she adds with a smile, “because this little trickle can quickly turn into a torrent and then we have to crawl across using a ladder.”

So a location not without its challenges. And though a couple of telegraph poles suggest this wasn’t always the case, currently off-grid.

“It was built in the 1940s as a smallholding so originally it was home to a family who farmed the surrounding land. But in the intervening years it ceased to be lived in year round and then it was sold to the elderly couple who were looking for a summer cabin. Which made agreeing terms fairly straight forward as it was sold-as-seen and the only delay was having to post documents back and forth as the vendors preferred not to use email.”

Having to resort to a small petrol fuelled generator for their electricity supply—an array of solar panels with battery storage is high on their list of priorities—they do however have access to fresh water in the shape of a pipe that feeds from higher up on the hillside. And following a first weekend devoted to cleaning—dust, dirt, dead flies and a few mouse droppings—they made the decision to finish off the renovation work to the upstairs sleeping area that the previous owners had already started.

“Luckily my parents are both retired and were able to help,” mentions Henna. “Dad taught me how to render the chimney and also helped carry all the tools and cement from the car. And then we started sanding the bedroom floor which was pretty straightforward but took forever and also coincided with a heatwave of 30°C. But I guess that’s the reality of restoring a property. When the sun shines and there’s surf, you’ve still got jobs that need doing.”

Working on the interior

Click an image to open gallery

When not hunkered down stripping layers of sticky oil paint off the upstairs floor, they also spent time outside working on the garden. A term, laughs Henna, that she uses in its loosest sense.

“We trimmed back two smaller trees that were rubbing the cabin’s walls and windows—much like a windshield wiper when the wind blew—before switching focus to an area of uneven, tufted grass immediately outside the front door. Peeling away this top layer, underneath I discovered a lovely terrace constructed from flat stones. And once you start it’s kind of hard to stop as you keep making these surprising, if backbreaking, discoveries.”

Surrounding the cabin, partially hidden under grass and moss, one of these discoveries was a barbed wire fence—long neglected and collapsing in places—which they decided to remove. Only to realise, later on in the summer, that it did actually serve a purpose when they found sheep droppings all over the terrace outside their front door.

Having now added install a new fence to their to-do list, Henna mentions how one item was an immediate and foremost priority from their very first site visit.

“The previous owners had rather an interesting toilet solution that we, very quickly, decided needed addressing.”

Here, my interest very much piqued, I prompt Henna to fill in the details.

“Imagine a bench with a toilet seat-sized hole cut through and a plastic bag hanging down underneath. Which is bad enough but what do you do with the bag once it’s full? You can’t tip it into the stream, you don’t really want to bury it, so the only other option is to carry it back to the car. Which would possibly cause a few raised eyebrows when meeting any passing hikers.”

And the answer, I’m eager to hear?

“There is a Finnish brand of composting toilet that my parents have at their summer cabin. Relatively compact and smell free but super expensive to purchase in Norway. So we asked my parents to come and stay and would you mind ever so much bringing us one of these toilets.”

Getting to grips with the ‘garden’

Click an image to open gallery

With their toilet situation sorted, the focus can now switch to providing an alternative to their current method of showering.

“When the weather is warm we just shower outside under a hose or in the stream. If it’s a little colder, we use a system of buckets and some boiled water. So quite rudimentary but it’s a temporary fix and next summer we plan on building an outside shower that’s at least sheltered from the wind and offers some privacy. As opposed to me and Adam jumping around naked outside. But our dream is to empty the shed and convert that space into a sauna, washroom setup. But this part of the renovation project is on hold whilst we cost the removal of the asbestos ceiling.”

With a kitchen comprising a sink where they can wash dishes and an old gas cooker that runs off bottled propane, Henna suggests that the simpler they make everything, the less likely that things will go wrong. But as to the realities of undertaking such an extensive and remote renovation project, she’s quick to concede that they have experienced difficulties.

“When my parents first came to stay, the weather was horrible. So windy they thought the cabin was about to get blown away. So one reality of owning a cabin on the west coast of Norway is that it’s not always sunny. And like every renovation you see on TV, everything takes way longer than you originally think. So we’ve definitely had our moments of stress but you very quickly discover that it helps—if you can—to just accept the slower pace that an older property determines. Because it was always meant to be a fun project and so you learn to be patient and adapt your plans as things move along.”

As for what Henna is most looking forward to over their second year of ownership, the ongoing process of transforming this space—and in doing so, fitting it to their needs—is clearly what’s motivating her to continue the renovation.

“The upstairs is pretty much done, so this year we start work on the downstairs. Our plan is to take down one wall and combine the kitchen and living room into one big space. So I’m looking forward to getting this second phase started and what makes it all especially exciting, is that for so much of my professional life I’m sitting in front of a laptop screen. At the cabin we live super simply and get to work with our hands. Yes, we could pay someone else to do the work for us but the physicality of the process is something we both very much enjoy. Previously I’ve renovated my van Eldo which taught me so many new skills but this is the first time I’ve fixed up a house and that prospect is super exciting.”

Even the floor sanding, I can’t resist asking?

“Looking at the result? Yes, even the floor sanding.”

All imagery with kind permission of Henna Palosaari and Adam Gairns