A couple of years ago, I’d arranged to interview Rapha’s Head of PR at their Imperial Works headquarters. After entering the building down a ramp with employees wheeling their bikes to the waiting storage area, we joined the queue for coffee before climbing the stairs to a large open plan work area. During the various introductions to different operational teams, I can remember passing a section of the floorplan closed off with tall curtains. Intrigued, I slowed, only to be led away with a few hushed words of explanation. ‘Oh, that’s just design.’

I’ve always assumed that this understated remark was simply their polite way of diverting my attention. Because judging from the number of product launches we see in response to each new cycling season, clearly these designers are kept busy. But what, in effect, do they do?

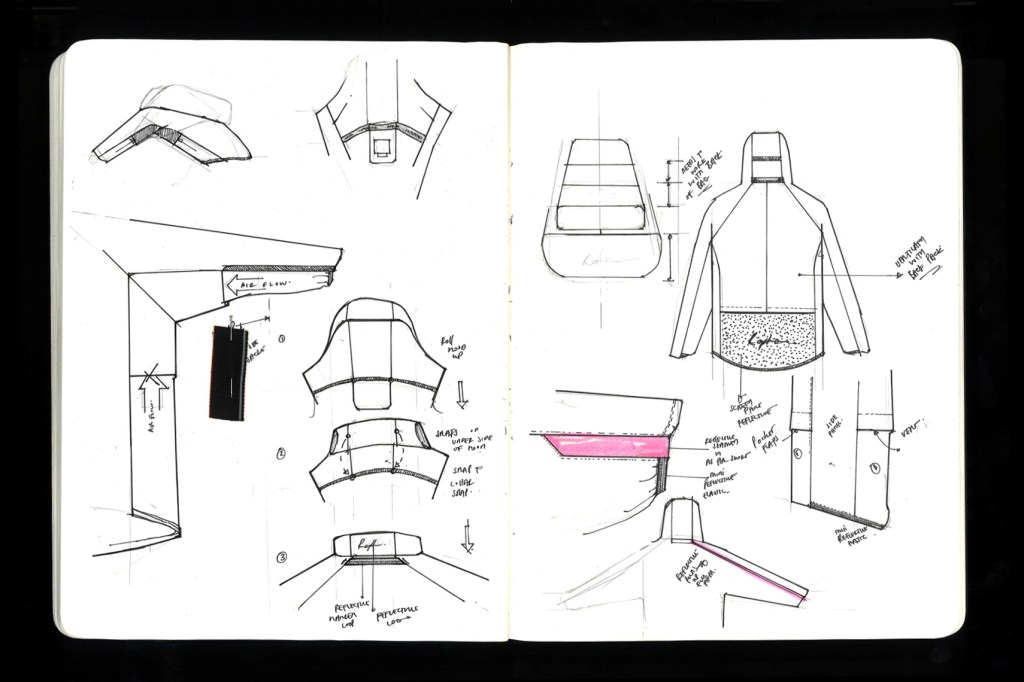

Responsible for the design of Rapha’s recently launched Lightweight Commuter Jacket, James Pawson has a passionate understanding of the creative process in his role as Product Designer with the London-based company. And in telling the behind-the-scenes story of this particular piece, perhaps offering us an insight into what lies behind that curtain…

It’s important to understand the problem. And because I’ve lived and commuted in London for close to 10 years, I kind of knew what this piece needed to do. It’s a challenging environment for riding so visibility in both daylight and into the evening is a must. And it was also about nailing the fit; ensuring there’s a balance between form and function. A focus on detailing that I think it’s fair to say Rapha has a reputation for.

So from this starting point, you marry the needs of the customer to how they will wear the piece. And having used the original jacket on my daily commute to work, I was aware of certain design aspects that I wanted to revisit and refine. We’re very fortunate to have our own atelier where pattern cutters and machinists can run off these little 3D mock-ups of maybe a cuff detail, a hood or a pocket opening. Allowing me to play around before building these separate parts into the design of the final product. Trying an idea, getting it out on the bike and seeing if it works.

To me, this questioning attitude is fundamental to the role of a designer but I am aware that I drive my team crazy because I’m never satisfied; always wanting one more prototype [laughs]. But at Rapha, that’s kind of expected. Never leaving any stone unturned in a quest for the best a design can be. And if our customers could actually see the amount of work that goes on behind the scenes, I’m sure they’d understand why we always try to take our products to the next level.

Moving forward from this initial concept stage and addressing the technical aspects of the design, the elasticated cuffs, hem and hood all have three yarns of 3M reflective knitted in. The round reflective patch on the rear of the jacket originated from our story labels but was simplified down and externalised to not only be functional but to also incorporate the ‘Made You Look’ tagline. In terms of placement, you’re always going to need the reflectivity on the lower back so we positioned this to be visible below the bottom edge of a backpack and level with the eye line of car drivers. A design concept I put to the test riding home with a colleague of mine when she must have got some funny looks; sitting on my wheel taking pictures of my rear end to document the placing of the various reflective elements.

Sometimes this process can be product specific. You take the Classic Jersey, for example, and we can only go so far from that particular brief. But with other lines, we have quite an organic approach and it’s fun to see where it takes you in terms of the look and feel. For this jacket, I knew it had to come in at under £100 and include x, y and z in terms of features. So it was my job to make that happen.

Design doesn’t happen in isolation and I’m also working on the next generation of waterproof commuter jackets. We envisage these two garments sitting side by side and complementing the different international markets. There’s the west coast of the States where it doesn’t really get cold or wet enough to ride in the waterproof piece but then we have the European and Far East markets where the climate means a fully waterproof version sells well. And it’s the same with colour. The ones that pop really resonate in Australia, South Korea, Japan and the West Coast. Whereas in the UK we love a muted black, navy or green. So we try to ensure we’re offering a decent range of choice and these decisions are very much influenced by the insights we get from our worldwide network of clubhouses and our regional managers. A little nugget of information from Taipei or a suggestion from San Francisco can be invaluable and helps balance what the customer wants with showing them something new.

Looking at the design process in its entirety, the very beginning and very end are for me the most satisfying. When you start a new project, at that point you’re at your most creative with a period of time to try out new concepts and ideas. A really exciting search for solutions that can even challenge what the team expect you to come up with. And then on the flip side, when you finally get to see your design being worn by someone. Maybe on your commute or riding around Richmond Park; to understand that hard-earned cash has been spent on a product that you’ve designed is so rewarding.

Not that every decision works out though. And as much as I hate it when this happens, you have to accept that failure is an important part of the design process. Sometimes you need to acknowledge when you’ve reached a deadend and it’s a case of, right, how can we start again? There’s always lessons to be learned and you’ve just got to be quick to react to them.

As a designer, I find how you soak up information is constantly evolving. I graduated less than 10 years ago and in that relatively short time, the influence of social media has become increasingly important. You need to be aware of it to ensure your product is culturally relevant but still balance this understanding of what everyone else is doing with your own references and how you choose to interpret them.

In terms of the manufacturing side of things, we also need to consider how environmentally responsible we are in our designs. Especially as we sit first in the consumer journey. If we really own those decisions by producing quality products that will last or maybe pushing to use a recycled fabric or zipper; then hopefully it will have a ripple effect across the industry and the customer will grow to expect that level of change.

Which colour of Lightweight Commuter would I choose? My original research referenced a piece from the Rapha & Raeburn collaboration. An amazing jacket in recycled parachute silk with this vibrant colour scheme. So I’d go for orange because it’s really visible when I’m riding to and from work. And it still looks cool if you want to wear it out around town [laughs].

Research and sketchbook images by James Pawson

Photography with kind permission of Rapha UK