Photography, home renovation, cookery, bike building…

I’m on a call with Donalrey Nieva, reeling off just a few of the disciplines in which he excels and wondering whether there’s anything he can’t do?

“Lots of things,” responds Don with a self-deprecating laugh; before explaining, when quizzed on this question, how he jokingly describes himself as a professional amateur. Which, to me, only suggests that I’m not the first person to comment on his multiple proficiencies. But I decide to let this slide; preferring to fill in the broad strokes of Don’s background before we focus more on what makes him tick.

“I was born in the Philippines and came to the States when I was 11. Growing up, it felt like a pretty normal childhood. I was into video games and stuff like that but funnily enough didn’t know how to ride a bike. So I guess you could say I was a late bloomer in terms of cycling.”

Describing how he would skip school to play Zelda on the Nintendo, when he was a little older and encouraged by his brother, Don remembers getting into aspects of hip-hop culture like graffiti and DJing.

“We were pretty close growing up,” Don explains, “so whatever he did, I copied.”

Settling in Las Vegas—Don already had aunts and uncles who’d moved to the city during the 60s and 70s—I’m wondering what it was like, growing up in such an iconic location?

“It’s a common question that I get from people and I usually preface my response by asking how much time does a native New Yorker spend in Times Square. Because I lived in the suburbs and one suburb is pretty much like any other in lots of ways.”

When he did get into cycling it was mostly BMX but only after an extended period of hiding the fact that he couldn’t ride a bike from his friends.

“They’d all be hanging out in the neighbourhood, learning tricks, and I’d be inside playing video games and feeling a little ashamed. But my Mom noticed what was going on and started taking me to this stadium that had a large, empty parking lot where I could practise. She had me riding my sister’s bike—a fluro pink frame with tassels attached to the handlebars—and it took a month of weekends with me complaining, complaining, complaining before I noticed my Mom had taken her hand off the back of the saddle as I pedalled.”

With bikes now firmly established in Don’s burgeoning list of interests, a family trip to Hawaii took riding to another level when he hooked up with Justin, a friend who was into streetwear.

“We’d arranged to meet and Justin rolled up on a track bike which looked so cool. And it wasn’t just any old track bike; this was a Japanese NJS import. So as soon as we got back to Vegas, my brother bought a really cheap fixed gear bike. And where he led, I eventually followed.”

People and the city

Click image to enlarge

With photography now such an integral part of how Don enjoys his riding, perhaps surprisingly it wasn’t until college that he first picked up a camera. Planning a trip to New York, his friend suggested that it would be fun to take some shots when they were walking around Manhattan. But even though Don understood how this offered another outlet for his artistic energy, it was a slow burn and not something he remembers taking too seriously.

“That didn’t change until I officially moved to New York in 2019. Blogging and sites like Tumblr were catching on and this trend in sharing content helped encourage me to document my everyday life. Mostly images of me and my friends riding track bikes around the city and the parties that we went to.”

With his imagery developing a very distinctive look and feel—think refined tonal quality with a masterful manipulation of depth of field—Don suggests that stylistic growth is ever evolving if you continue to question the process and take the time to appreciate the work of other photographers. But interestingly, he baulks at the suggestion that professional quality content requires a certain specificity of equipment.

“Sure, the gear matters. But, at the same time, I’d say that sixty percent is down to the photographer’s eye. Like when I always used to carry a big DSLR with a couple of lenses when I was shooting a trip—which meant a lot of weight to lug around—but now I ride with a super compact Sony RX100 Mark VI which takes really great shots.”

This mention of the trips Don has taken—camera to hand—nudges our conversation along to his riding and how it’s developed over the years. For such a self-styled late bloomer, he’s certainly made up for lost time with a catalogue of epic adventures.

“When I first moved to New York, the bike offered me this freedom to explore. You can see so much more compared to walking or taking the subway. And then this extended to wanting to ride out of the city; seeking out all these unknown roads and trails which was a relatively new way of riding.”

So when does a ride or route become epic, I prompt?

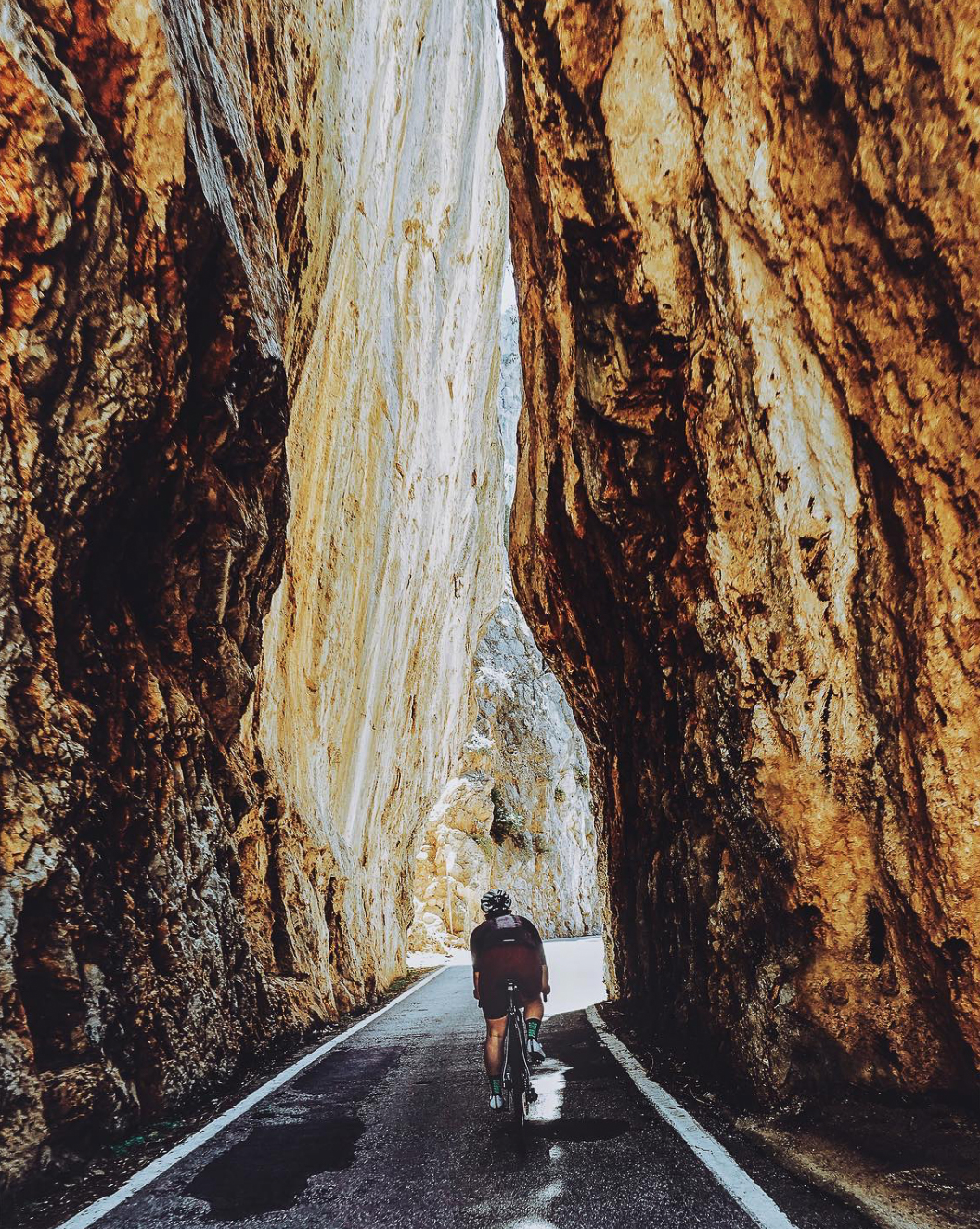

“If something goes wrong?” is Don’s considered reply. “Which maybe, at the time, doesn’t make for a particularly easy or enjoyable experience but, looking back, offers you memories that will last a lifetime. Like when we took a trip to Sri Lanka—my first time riding there—and I made the route using RWGPS. I could see all these squiggly roads which usually means a lot of climbing. And I just thought, fuck it, let’s include these sections and see what happens and they turned out to be some of my favourite parts of the trip. So sometimes you just have to go for it. Maybe it’s rideable, maybe it’s not. And if it’s not, then it’s an adventure, right?”

Karen

Click image to enlarge

This propensity for pushing past what can comfortably be achieved is no better illustrated than on a trip to Colombia with his then partner, now wife, Karen.

“That was back in 2018 before the current boom in riding offroad. I’d set my heart on climbing the Old Letras Pass which they now call Alto del Sifón. A 115 km climb with 4700 m of elevation and, at the time, half of it unpaved. So a big day—the reason we set out at 4:00am—but with a consolation prize of a really nice hotel located a few kilometres on the other side of the summit.”

“It was still dark when we started riding and the rain was pouring down but it wasn’t super steep so we were making good progress. Eventually it dried up and we stopped at a town for some food before the dirt section started. And what’s funny is that looking back at it now, Karen and I have very different memories. I thought the surface was okay but she remembers it as being pretty rocky. But whatever we thought individually, we were riding much slower than I’d anticipated and the sun was starting to set when we still had a ways to go to the top. That’s when I discovered that the morning rain had destroyed my light and Karen took a tumble on the loose surface. At that point, in my head, I was wondering whether we’d have to spend the night on the side of the road.”

“But we kept on riding and did eventually reach the top; just as our one working light started to flicker. I knew we only had 5 km to go, downhill, to the hotel. But in the dark, with no lights, it was simply too dangerous to carry on. And then, as if in answer to our prayers, a car came round the corner. We flagged it down, explained our situation as best we could, discovered that they were also staying at the same hotel, and then set off riding down the mountainside with the car headlights illuminating our path from behind.”

Whilst certainly qualifying as epic, what I’m yet to fully understand is how this ride connects with their own journey as a couple.

“After we checked in and got to our room,” Don continues, “Karen just burst into tears and, because she was crying, I also started crying. Our reactions quite possibly prompted by this being our first overseas bike trip together and a pretty memorable one at that.”

Travel

Click image to enlarge

Not that Don’s relationship with riding is confined solely to foreign climes; his connection with The 5th Floor coming about following a trip to LA with friends who raced and the suggestion, over a group text, that maybe they should start a New York chapter of the cycling collective.

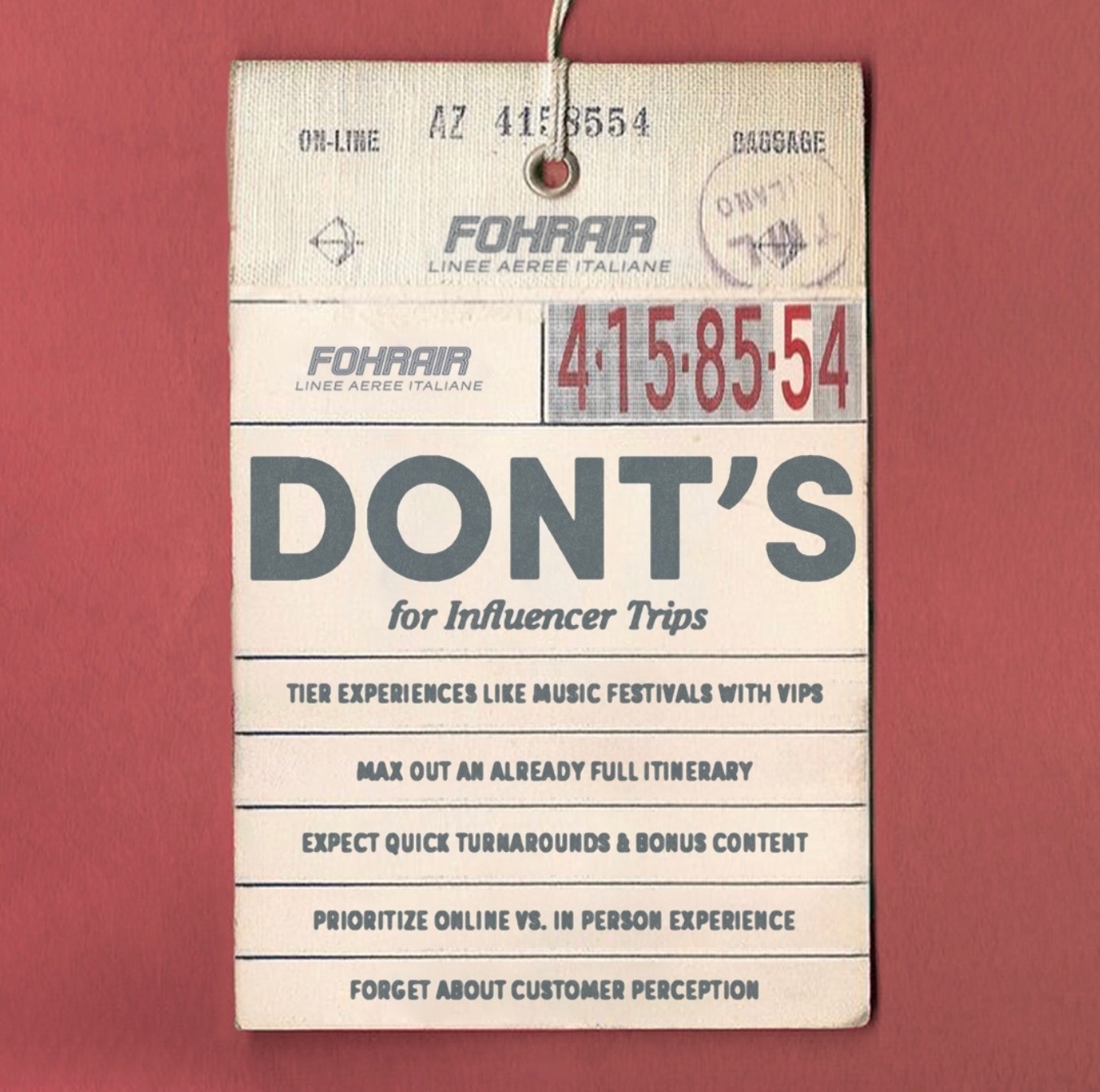

“Racing wasn’t really my thing but with Adidas, Wahoo and Specialized onboard as sponsors, I was happy to help out The 5th Floor team with photography. And all this coincided with an interesting time in brand marketing when we took a trip out to California for the launch of the Specialized Diverge. After we’d finished test riding the bike, the head of marketing was discussing content creation and coined the term influencer. That was the very first time I’d heard it used and, to be honest, I thought he was joking around; casually suggesting they provide bikes in exchange for us contributing words and pictures for their online blog. And this all happened way before Instagram became a thing.”

Supported by Specialized he might once have been but there’s no hint of carbon in his current stable of bikes; Don favouring steel and titanium and not shying away from a statement build if the recent pictures of his re-finished Firefly are anything to go by. Which begs the question whether gold is now his favourite colour?

“It is not,” he fires back with a laugh. “I guess I wanted something that was pretty unique and would complement my other Firefly which is finished in bronze. And then, when they sent me a photo, I was like, oh shit, that’s really gold. But now I’ve grown to love it.”

Bikes

Click image to enlarge

Having ridden with Don in Portugal on some pretty insane trails—he’s an accomplished bike handler when things get a little rowdy—I was left wondering why there’s no hardtail or full sus in his bike collection. The answer, perhaps rather prosaically, being that they’ve never really piqued his interest and that the older he gets, the more concerns he has over falling and breaking something. Add in the fact that he lives in Brooklyn—at least from Monday to Friday—and I’m wondering if that might also dictate the style of his leisure riding?

“The community is fairly small but that just means you know everyone. And Prospect Park is a convenient place for me and Karen to ride with friends.”

Going by their Instagram feeds, café stops appear to play a big part in the couple’s ride routines. And causing me to inwardly wince whenever I spot the price of the pastries they’re ordering.

“The café scene is mostly Karen but it’s also a fun part of our riding. And yes, it’s crazy how expensive it is here. I don’t drink coffee but even a matcha latte is around $8 for a small cup. But our apartment is close to some super nice bakeries and I sometimes wonder if people understand how much work goes into making a croissant.”

With weekdays seeing Don commute by bike over the Queensboro Bridge to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center where he coordinates research projects, weekends often find him in the Catskills at Highcliffe House; the chalet that he and Karen bought in 2020 towards the tail end of the pandemic.

“We never actually planned to buy anything upstate. But it was a region where we enjoyed riding and we’d catch the train up there fairly regularly. And then during the pandemic that just wasn’t feasible so we ended up borrowing Karen’s parents’ car which turned out to be super convenient. Especially that summer as everyone seemed to be doing really big rides. It became a thing that you rarely covered less than 100 miles and I remember one time when we were driving back to the city and I mentioned to Karen that it would be kind of cool to have a place upstate. I was joking but the seed was planted and we decided just to look. But once we started looking, we saw properties that we liked and after a couple of months closed the deal on Highcliffe.”

Comparing its renovated state on Instagram to some earlier photos, it’s clear that a lot of hard work has been invested.

“It was built in 1980, had orange and blue carpet, and really ugly wood panelling that looked like it was infested with termites. And looking back, it seems very daunting to take on such a huge renovation project but when we first moved in, our plans only extended to a couple of coats of paint and changing the floors. Little did we know.”

Highcliffe

Click image to enlarge

So an enjoyable process or more of a means to an end?

“There was a lot of learning required—a lot of watching YouTube tutorials—but I personally enjoyed it. Perhaps because I like working with my hands which stems back to my artistic interests.”

Not only does the unpaved road that leads up to Highcliffe prove a challenge for vehicular traffic when the winter snows arrive, it also boasts its very own Strava segment.

“It’s a private road and unmaintained,” laughs Don. “Just shy of a mile with sections of 20% and it’s a standing joke that all of our house guests that ride have to attempt the hill climb at least once.”

With an interior fashionably furnished with a discrete smattering of design classics, I’m wondering whether Don is still collecting Facebook Marketplace finds on his Brompton?

“That’s one of the great things about NYC. How there’s so many wealthy people who are constantly moving and want to offload really expensive design pieces. And the Brompton? I did have one particularly tricky ride home with a floor lamp balanced just above the front wheel. And you know how twitchy Bromptons can be.”

Considering the active social life the couple enjoy in the city, perhaps it’s a little premature to ask whether Don can ever see himself living full-time at Highcliffe. But he clearly relishes the peace and quiet afforded by such a rural setting; a bucolic lifestyle enlivened by visiting family and friends. Or garden parties, I add, referencing the celebration of their wedding in 2023 following an exchange of vows at City Hall.

“Cycling is such an important part of my life; pretty much the reason why I moved to New York which I guess is kind of stupid. Usually people relocate to start a new job but I wanted to ride my track bike in NYC. So to have someone special like Karen to share all that is really great. And it’s already a given that any trip we take has to be a bike vacation.”

So you first got to know Karen through riding bikes, I ask?

“We met through mutual friends but I already knew her from Instagram. And I remember egging on my friend Julia to make sure she invited Karen along on the rides we were planning.”

So an instant attraction?

“Absolutely not. Karen was tough,” Don laughs. “I was pursuing her for over a year.”

A year is quite a long time, I suggest?

“She knew that I liked her but she just wasn’t having it.”

So what changed, is my next question?

“Maybe you need to ask Karen,” replies Don with a smile. “I would arrange a bike ride and hope that it would be just me and her but then Karen would mention that we were meeting one of her friends at this or that corner. So eventually I started to question whether I was getting anywhere and decided to stop trying to hang out with her off the bike. And I think she noticed this change and we finally got together.”

Brand photography

Click image to enlarge

With this talk of sharing a life with a loved one and conscious that Don previously mentioned how formative he found the influence of his brother Kuya Gerrard*, I decide to tentatively touch on the tragic accident in 2020 that saw Gerrard lose his life on an organised bike ride. A loss that Don lovingly acknowledges in the messages he posts on the anniversary of his brother’s passing and in the physicality of shared passions.

*The appellation Kuya means older brother in Tagalog and is used as a sign of respect.

“I have his vinyl collection at Highcliffe. We both grew up listening to the same music so I’ll just pull out a random record and, in my head, each selection brings back a very particular memory. It’s a good trigger.”

And Gerrard’s name anodised on Don’s Firefly stem?

“When I’m out on the bike I’m always thinking of him, so having his name written there just resonates.”

Understanding that these material things offer a sense of comfort, I’m wondering what the objects are tapping into?

“Memories, I guess,” suggests Don. “Past and future memories.”

So if Don was to make a future memory? If he was to plan a pretty perfect day?

“It would have to involve a ride, for sure,” he confirms, perhaps unsurprisingly. “So out on the bike, exploring?”

Alone or riding with someone, I’m interested to know?

“Karen and I did the Torino-Nice Rally route and on one of the days we were pushing on to make it to the B&B we’d booked. Karen had taken a shortcut to avoid this huge climb but I didn’t want to miss it. And I remember being all alone, just me and my thoughts, climbing this mountain and thinking about my brother. So hypothetically? If my brother was with me, it would be nice to ride with him again. That would make for a pretty perfect day.”

All photography* with kind permission of Donalrey Nieva

*Feature image by Nik Karbelnikoff