They say if you do what you love, you’ll never work a day in your life. Which on the surface makes sense but is perhaps an oversimplification when applied to the world of media? Add in the filter of cycling media and oftentimes things become just that little bit more challenging. The grind as John Watson describes it.

Founder and co-owner of The Radavist—a platform relatively small in terms of staffing but one that punches way above its weight—this curated collection of photographs, features, stories and product reviews offers a well respected and much loved window on the world of alt-cycling.

Conversationally candid and never shy of courting controversy, John takes time out to explore life’s ups and downs: what keeps him awake at night, how his kitchen table doubles as editorial desk, and why, when all is said and done, it all comes back to a simple love of riding bikes.

cyclespeak

I see you’re starting the day with a coffee.

John

My second cup. It’s funny that when it gets really cold here, I just don’t want to get out of bed in the morning.

cyclespeak

So how cold is cold?

John

At the moment it gets down to negative 12 most nights. And that’s Celsius.

cyclespeak

Pretty cold.

John

We’re at 2300 metres. So kinda high up in the Rocky Mountains.

cyclespeak

When you’re home in Santa Fe, is there a regular rhythm—a routine—to your day?

John

If I’ve been away camping, then my circadian rhythm has me awake by five thirty or six. But aside from that, most mornings I’m up around seven. I’ll drink some water, do some push-ups, make a coffee before sitting down in front of my laptop to check whether there are any fires on the website that need dealing with. Then I’ll work on the Radar press release articles, check on my emails, and do some writing until around noon when I try to get out on the bike for an hour’s ride. Once I’m back home, I’ll finish up any features, hit publish, and then it’s time to start preparing dinner.

cyclespeak

That all sounds pretty dialled.

John

We’ve got a good system editorially at The Radavist. Everyone works freelance but amongst the assigned roles, we have what I like to call a foundational editor who combines the text and photos to build a particular feature. Then the copy editor takes a look to make sure there are no grammatical errors before I give it a final check, do all the SEO stuff, and schedule it. Where it can get a little hectic is when me and Spencer are both on the road—maybe in different time zones—but I feel that’s just the nature of being a scrappy, small publication. I think it’s fair to say we’re pretty influential but our physical footprint in terms of staffing is very small.

cyclespeak

Occasionally you share photos of you and Cari at home in Santa Fe. Out doing chores by bike, the recent garden project, your workshop tidy. So what forms your sense of home? Is it rooted in a particular location, the possessions you have around you, or maybe a certain way of living a life?

Home (and away)

Click an image to open gallery

John

Back in 1976, Edward Relph wrote an essay on Place and Placelessness—this goes to my architecture background—which touched on the concept that a house isn’t necessarily a home. And for me, this space I share with Cari in Santa Fe is both a home but also our office. Maybe someday we’ll invest in a separate space to work out of but that’s an extra expense that at present we don’t want to take on. And then you add to this physical space our tendency as a couple to nest. We spend the day working 20ft away from each other which makes me smile because I have friends that complain if their wives decide to work from home and they just can’t stand being in the same space together: they get in arguments all the time. Which perhaps might account for all the divorces that happened during the Covid lockdowns?

cyclespeak

And you two together?

John

I’m just really lucky to have a partner willing to put up with all my bullshit.

cyclespeak

That’s a nicely nuanced way of putting it.

John

Cari is super supportive and over the years has really gotten involved with the website on a day-to-day basis. Perhaps prompted by this being our only form of income.

cyclespeak

I get the occasional reference to it being a financial challenge.

John

It’s working but maybe not on a sustainable level. We can cover our bills but there’s not much left over to add to any savings. And that’s a little scary when you consider making plans for retirement. But house, home, place? I definitely feel comfortable here because it has a wide open floor plan that suits our needs. We don’t have kids and most of the space is filled up with bikes and plants; a bike in every room kind of thing. We bought the ugliest house on the block but then my architecture and construction background helps. Our plan some day is to take out a HELOC loan—which stands for home equity line of credit—that would allow us to extend the house, maybe add a home office, so that there’s some sense of separation.

cyclespeak

Like those individuals that work from home but have a dedicated room for that purpose where they go to work.

John

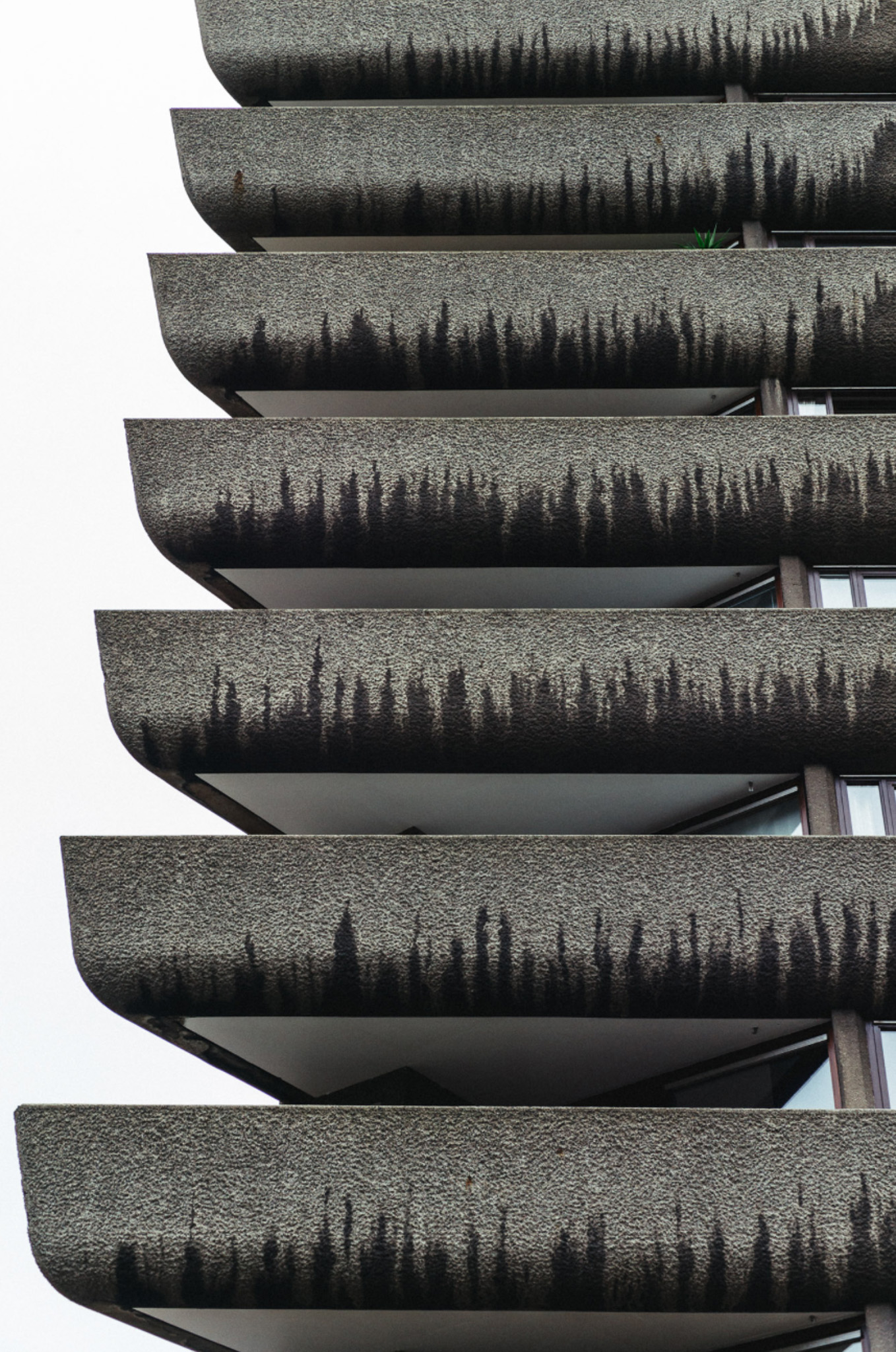

Cari has a little room. But saying that, it also contains our bikes and ski stuff, her artist materials, my tools. Whereas I work sitting at the kitchen table or on the couch. Which might explain why I tend to head out to get a coffee or go for a ride around midday. I was reading about this physiological study that was suggesting how 15 minutes of riding a bike unravels seven hours of sedentary behaviour. Similar ideas that this book I’m reading at the moment addresses—the Comfort Crisis—which talks about our detachment from nature and the gains to our physical and emotional health this prevents. So even if I can’t spare the time to get up in the hills and off the beaten track, my ride to the coffee shop passes through a bunch of trees which kind of scratches that itch.

Landscape

Click an image to open gallery

cyclespeak

As both you and Cari are so invested in The Radavist—both personally and professionally—would you say that’s a strength because you each intrinsically understand the challenges that come your way? Or do the lines between work, home, the two of you as a couple, ever become blurred?

John

Quite a harsh blurring. And I think this maybe has something to do with a certain mindset which allows you to clock in and clock out. But that’s definitely not me.

cyclespeak

It’s not?

John

I don’t think anyone would want to hire me for a corporate position. I’m not really cut out for the survival tactics that come with all that. Looking back to when The Radavist was part of a larger corporation for two years*, I couldn’t believe how completely detached from reality their internal structure was. It was all about ensuring you still had a job and not so much about actually doing the job. Whereas I see myself—I was born in 1981—as more of a hustler. My parents didn’t come from money, there’s no trust fund waiting for me. Which means I’ve literally got to grind and my entire life becomes my work. And maybe that’s why our readership is so engaged with the site and people feel like they know me even though we’ve never actually met before. And what I find funny is the same thing is now happening to Cari. When we were walking around the Bespoked show in Dresden, I saw how they recognised her but maybe felt too shy to say hi. Which can be a little unsettling because there’s always the thought in the back of your head that you’ve just got something on your face.

*The Radavist merged with The Pro’s Closet (TPC) from October 2021 to October 2023

cyclespeak

I like that people think they know you.

John

We get a lot of messages about the road trips Cari and I take. Maybe because it’s nice to see two people so much in love and who care passionately about what they do for a job. A good, positive story in a world that’s rapidly caving in on itself.

People

Click an image to open gallery

cyclespeak

My wife really likes to talk about her day at work when she gets home; in quite extraordinary detail. So I was wondering where you and Cari sit on that spectrum?

John

I’m an April 23rd Taurus—Shakespeare’s birth and death day—so I’m very analytical and detail oriented. And I can kind of hold grudges a little bit—to say the least—so Cari and I can be sitting in bed and she’ll quite innocently just bring something up and, that’s it, I can’t sleep all night. I’ll toss and turn and it’s not like either of us are in this for the money. So there’s definitely an element of sink or swim which just envelops your entire life. Something we both talked about last year: about setting some boundaries and taking some time to work on ourselves as a couple, to do things that aren’t so work related. I mean Cari’s an artist and she wants to paint. She doesn’t just want to design socks.

cyclespeak

Because Cari went to sign painting school?

John

She’s so talented and it was cool to see her come on board in 2017. To see our merch go from being all drab and desert to actually having colour and typography. And what we have right now is a system where if we’re going over to Bespoked in the UK, we’ll fly out a few days early and take in some architecture and the museums. Kind of like taking an art walk with my camera.

cyclespeak

And Bespoked in Dresden?

John

We spent four days in Berlin before the show, which was fun. But saying that, it’s a hard city to shop in because I don’t dress like the people of Berlin.

cyclespeak

Does this same system also work in the States?

John

Say we’re going out to a race in California, we’ll take Troopy* and make it into a road trip: camping along the way and visiting some of our favourite places. Which is good but we haven’t taken a solid holiday—where neither of us open a laptop—in like, never. Even on our honeymoon—which we spent in France—we just stayed on Cari’s brother’s couch. And I was still working every day because we’re not financially secure enough to have full time people that can just take over the reins.

*John’s 40-year-old Toyota Land Cruiser

cyclespeak

You know, John, I didn’t realise you and Cari were married. I did hear you mention on a podcast that Cari gave you a rock, a flower, and a feather, before asking you to marry her. Obviously I missed the bit about you actually being married.

John

It’s not really something I flag up. And neither of us are very traditional in the concept of marriage; all that ownership bullshit that comes with Christian values. So I guess you could say she’s not my wife and I’m not her husband. We’re just partners—in both life and work—and that’s how we like it. If you strapped me into a chair and distilled every one of my moral and ethical boundaries, it would be more pagan than anything. So those gifts of Cari’s were more her version of giving someone an engagement ring. Objects from this place where we’d been camping for a few days that remind me of the bounty of that area: a beautiful turkey feather, a river stone, and a flower that blooms during spring.

cyclespeak

Are these on display at your home in Santa Fe?

John

Our house is just full of these little things that we find. And we’re both really into rockhounding, always on the lookout for minerals and fossils. Artefacts from previous civilisations— which we obviously leave on the ground—but it’s cool to find a spear tip that was once used to hunt with.

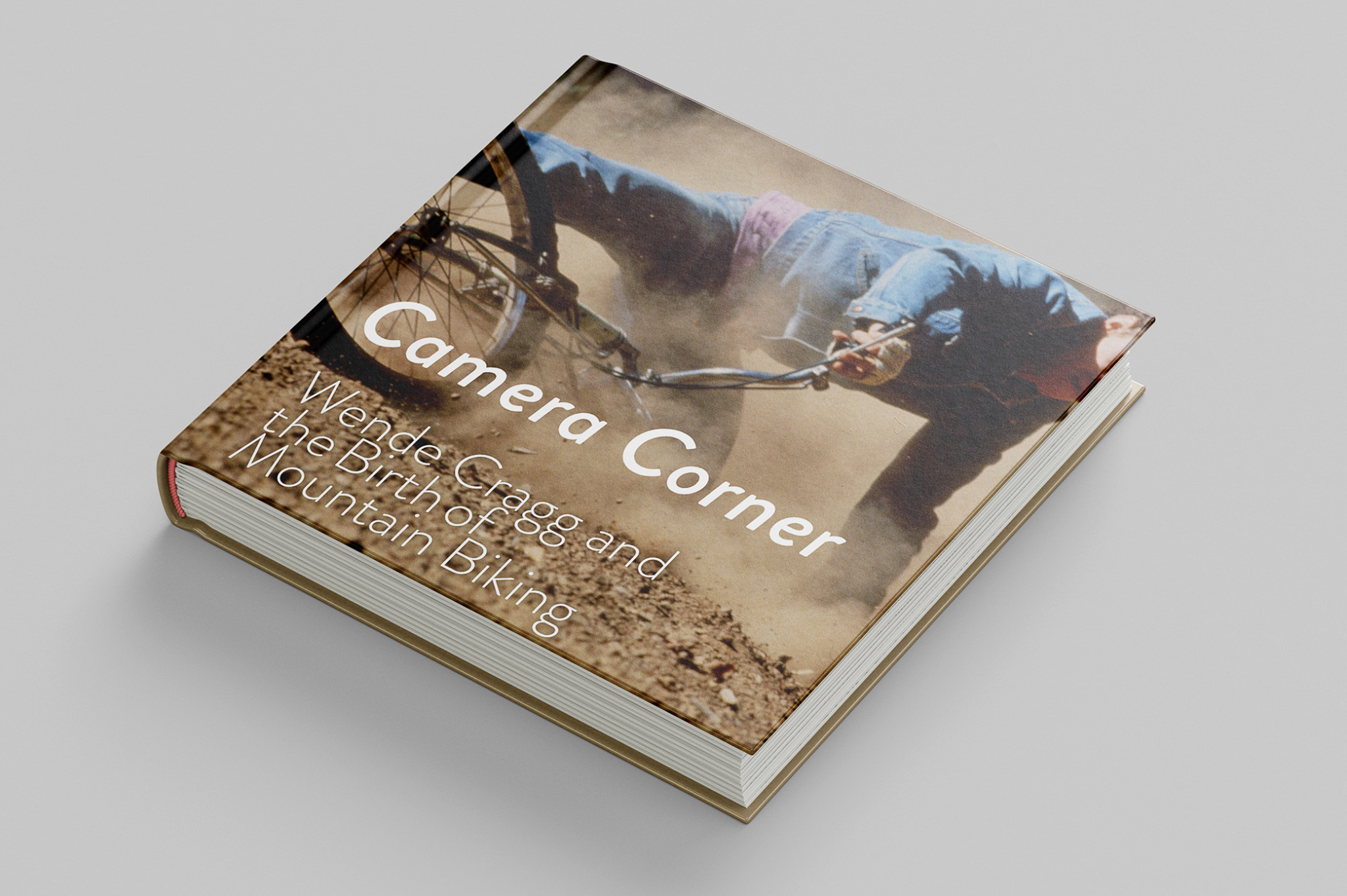

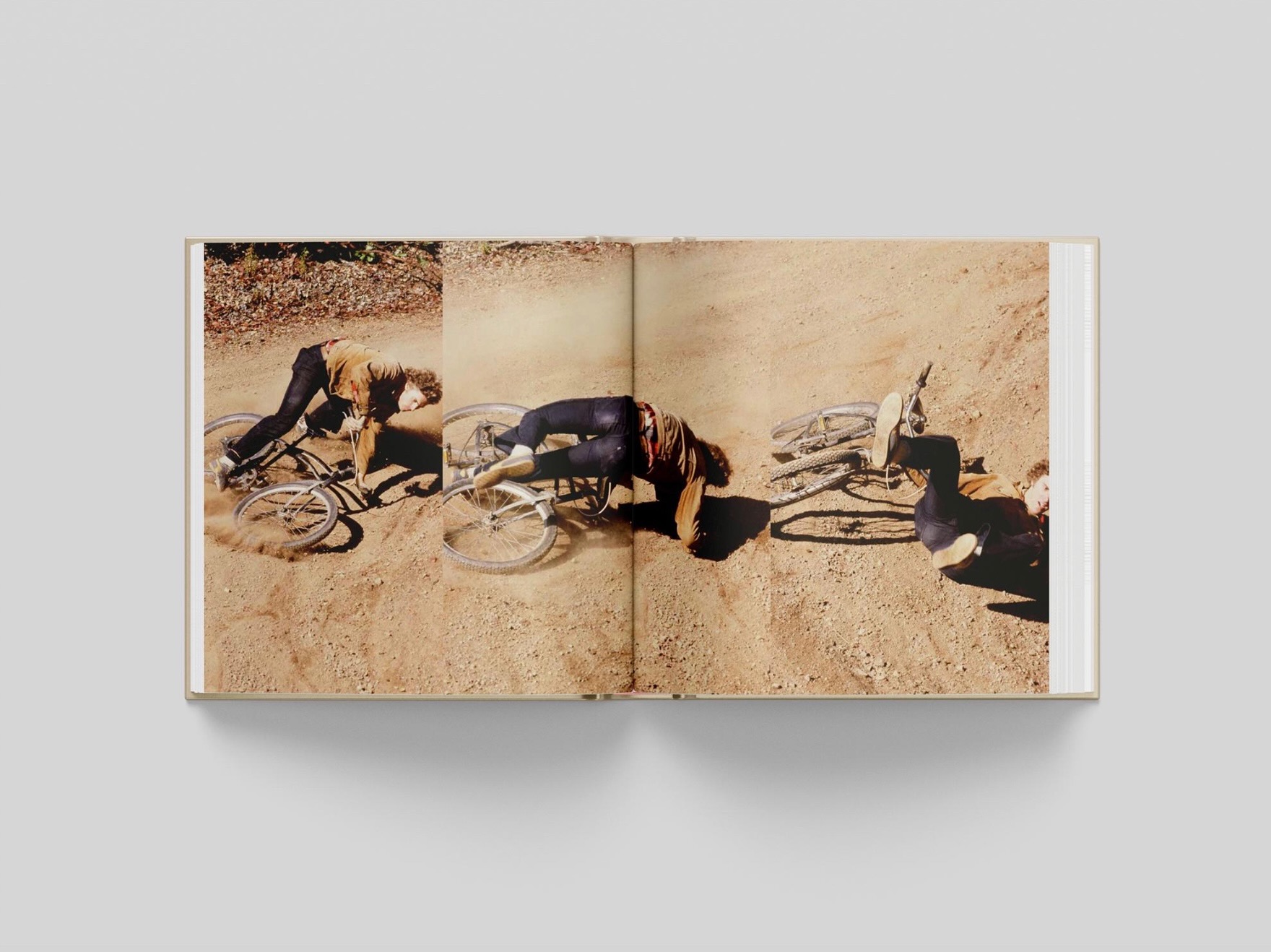

Camera Corner

Click an image to open gallery

cyclespeak

Speaking of the physicality of objects, Cari was principally involved in the publishing of the book Camera Corner. How did it feel for you to see this physical representation of Wende Cragg’s awesome photography put out into the world and know that Cari played such a paramount role?

John

Wende Cragg’s photographs document the birth of mountain biking. So for me, the fundamental core of this project was doing a story about a woman who was so influential. It’s about Wende—her imagery and the stories she’s written—and it’s about Christina Speed who did the book layout, and it’s about Cari who led on the art direction and design. And just being able to release this beautiful dove into the universe—that’s so full of positive energy and was basically created by these three women—was quite incredible. And knowing that dynamic, I really didn’t want to be a part of it. I even had a hard time writing the intro because it’s not about me. I just wanted to be there to help out if I was needed. Which was the case when there was a reference to a bullmoose bar and neither Christina or Cari knew what that was. So, yeah, it was super exciting.

cyclespeak

Creatively speaking, you’re a truly talented photographer, you write balanced and erudite pieces for The Radavist, and curate the most incredible bike builds. So I was wondering whether you’ve ever been tempted to pick up a brazing torch and fabricate a frame yourself?

John

First of all, thank you. But I don’t consider myself a great photographer or writer. I can look back on stuff I shot six months ago and I’m like, this is garbage. And I don’t know if that’s just my upbringing—always being told I’m not good enough—or if it’s seeing other people, elevated on a pedestal, that are years ahead of me. Yes, I can document landscapes and bikes really well but…

cyclespeak

John, I really don’t want to interrupt but when you did your Leica M10 review, those photographs of yours that you used to illustrate the piece were stunning. Beautiful landscapes but there’s a shot of Cari standing in front of some sign writing that’s so witty and artfully composed.

John

The Mojave one? Okay, I agree that shots like that take an eye. How there’s more to good photography than just picking up a camera and shooting something. But I still find I get to the end of every year and there’s maybe three images that I’m really proud of.

Cari

Click an image to open gallery

cyclespeak

I find this to be a common theme with the vast majority of creatives. They can be so analytical and are always questioning how they could do their work better.

John

It’s true that I’m very self-conscious about my photography and I’m very self-conscious about my writing. And I think that’s because I went through five years of architecture school, having my shit torn apart. Like, just relentlessly.

cyclespeak

That sounds pretty intense.

John

I think if half of these, quote unquote, Instagram photographers had to sit down and go through an actual critique in a university, after you’ve spent six hours in a dark room making a print, and then a professor just comes up with a fucking wax pencil and draws all over it, they would perhaps settle for an alternative career. And I hate the word trauma because sometimes I feel people conflate that with being uncomfortable. But that was some traumatic shit that happened, which is perhaps why in the back of my head I’ve always had this—don’t go in thinking you’re good—because your shit’s just gonna get ripped apart.

cyclespeak

And you have similar feelings regarding your writing?

John

I think people respond to the emotion in whatever I’ve written but it’s not like reading The New Yorker. There’s no prose. It’s just very matter of fact.

cyclespeak

I guess we write for different purposes. And I believe Ernest Hemingway once said that good writing is saying complicated things very simply. But I’m conscious we’ve come a long way from me asking you about frame building.

John

We sure have. And to answer your question, I would love to and I’ve put some serious thought into doing a frame builder course up in Portland. But, at the same time, I also don’t really feel the need.

cyclespeak

No?

John

I think this is—not a problem—but just one aspect of frame building. In the sense that not everyone who’s into beautiful handmade frames has to build one. Like, I love tattoos but I’m not gonna tattoo myself. And I think that respecting the artistry of what frame building is, in a lot of ways allows you to honour the craft.

Beautiful bikes

Click an image to open gallery

cyclespeak

So taking this one step further, when you’re looking at a really special bike build, what are your emotional triggers? Are we talking form, function, or a synthesis of the two?

John

If I was to be completely and brutally honest, right now it’s what makes a bike different from the sea of other things that look very similar. And in America, I think this is part of a bigger conversation. Builders like Rick Hunter—the fucking OG— and Todd from Black Cat are both doing amazing things. But generally speaking, there’s not a lot of innovation happening with U.S. frame builders. And I understand that’s gonna be controversial but off the top of my head, I can think of four or five bikes at last year’s MADE show in Portland that were stand-out different in the taxonomy of a gravel bike. A lot of people in the States are displaying tubes that are basically welded to Paragon parts with an Enve fork and a fancy paint job. And I get it. That’s what people want. That’s what keeps fabricators surviving in the States where there are very few subsidies for people who make things.

cyclespeak

Was it the same story when you visited Bespoked in Manchester and then Dresden?

John

I see the current state of frame building in the U.S. from a profit-based perspective. Europe is way more innovative. No one in the States is doing what Konstantin Drust is doing. Period.

cyclespeak

I saw your stunning images from the Dresden recap. Really wild designs.

John

Honouring it through photos—when I see something that is truly unique—is why I spend a good 30 minutes or so with a bike that interests me. And the reason I’m going to step away from shooting 50 or so bikes at MADE and really just hone in and shoot the bikes that I feel are innovative and truly representative of the builder. Which is easier said than done because there’s this expectation at U.S. shows that I shoot everything. Some of them thank me, some of them don’t, but at the European shows no one gets upset or writes an email bitching me out for not shooting their bike. No one gets angry that I’m somehow controlling the narrative of handmade bikes because I didn’t shoot this or that bike. In Europe people are just excited that I’m there. In the U.S., there’s this expectation that looms overhead.

cyclespeak

What puzzles me is that over here in England, it’s not uncommon to see price tags of nine, ten thousand pounds—sometimes even more—on a standard-sized carbon frameset, manufactured in Asia, with a mid-tier group set. Not that I have deep enough pockets to spend that kind of money on a bike. But if I did, the way my mind works would be to ask what that could buy me in a custom frame, built to my specifications, with a one-off paint design?

John

Ashley from Significant Other was offering titanium and steel full-suspension frames from $3,500 which is cheaper than any high-end carbon mountain bike on the market. And I guarantee you that bike is gonna ride way better.

cyclespeak

Not that we’re hating on carbon fibre—people can ride whatever they please—but surely there’s an allure to having something handmade?

John

I guess it’s the way consumerism works in the States and one of the biggest challenges we face with the website. You want to support these people making stuff in their garage. You want to support the innovators, and innovation is expensive. Bikes like the Apogee One—which is around $4,500 for a full-suspension frame—uses CNC and milling to create this bricolage bicycle inspired by a Suzuki motorcycle linkage. Which is why we gave it mountain bike of the year, because it’s the most fucking innovative thing I’ve seen someone in America do. And I think a lot of people look at an $8,000 handmade, full-suspension mountain bike and then they look at an $800 basket bike and they don’t understand the connection between the two. But fundamentally, they’re the same thing.

Architecture

Click an image to open gallery

cyclespeak

They are?

John

A human being took whatever technology was available and assembled something that made sense to them at that moment in time. Which feeds into this sense of identity politics that happens in cycling where your brand allegiance or style of riding becomes your identity.

cyclespeak

But I get that. Because even though we’re all just riding bikes, there’s this tendency to be tribal. Which explains why—from certain viewpoints—anyone wearing Pas Normal can get teased mercilessly. But it’s the same if you’re attending Ronnie Romance’s Nutmeg Nor’Easter. Everyone’s got a bar bag, metal bidons and there’s something dangling from their Brooks saddle. They’re wearing a uniform in much the same way as the Pas Normal crowd.

John

It’s like Freud’s narcissism of small differences. Where similar minded communities will rip each other apart over the slightest differences rather than embrace the things they have in common. And I wholly—one hundred fucking percent—blame social media for this. Back in the early noughties when I was riding fixed gear around New York City, we’d hang out with people on classic road bikes, vintage mountain bikes, guys into BMX. Joe from Brooklyn Machine Works would come out on his downhill bike and we’d ride through Central Park at night, jibbing lines and stuff because we didn’t have access to any trails. And when I lived in Austin, roadie guys riding bikes with an integrated carbon seat post would come out with me on my rigid Indy Fab—wearing shorts and a t-shirt—but no one really cared back then.

cyclespeak

And now everyone cares?

John

Which is so weird to me. Because I just like to ride bikes. All kinds of bikes.

cyclespeak

And why—along with The Radavist—you’re this touchstone for so many people also invested in riding their bicycles. Because I’ve personally witnessed how people greet and interact with you and I wanted to ask how this makes you feel?

John

For sure it’s a privilege. But one that I never really anticipated. Because this all started out of curiosity; back in New York where I saw all this stuff that wasn’t getting documented by mainstream bike media. Or if it was, it was a single image with a couple of paragraphs of text. A scene that I wanted to offer a platform because it was something I was truly passionate about and not something I ever did with the intention of it growing so big. I don’t even necessarily like having myself on the website but I enjoy making content and giving all these different communities a spotlight. So I guess with The Radavist now in its twentieth year, people do recognise me and want to say hi. Something that I take as a great honour.

cyclespeak

So looking back on the young man who’d recently qualified as an architect and was overseeing construction projects in New York City, riding his fixed gear bike, camera to hand; what do you imagine he would think if he could see you as you are now?

John

Hopefully that it’s a pretty good way to live a life. I have a house, I have a wonderful wife, I have a community of people who appreciate me. And I’ve got some fun bikes to ride and some cool cameras to shoot with. So everything on paper is pretty good.

All photography by John Watson (unless otherwise stated) / The Radavist

Feature image by Cari Carmean