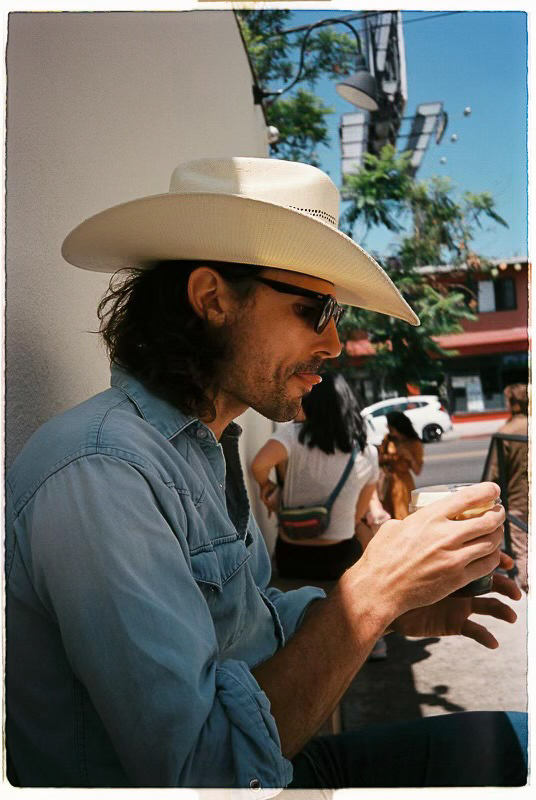

The last time Angus Morton and I caught up, he’d just dropped off his dog Terry prior to a trip overseas. We spoke for a little over an hour and the entire time he was driving his truck from one end of LA to the other. Almost two years to the day since that previous conversation, as our video call connects Gus is once again behind the wheel. But this time only for a couple of intersections before he reaches up to press the remote gate button and pulls into the parking lot of his office building.

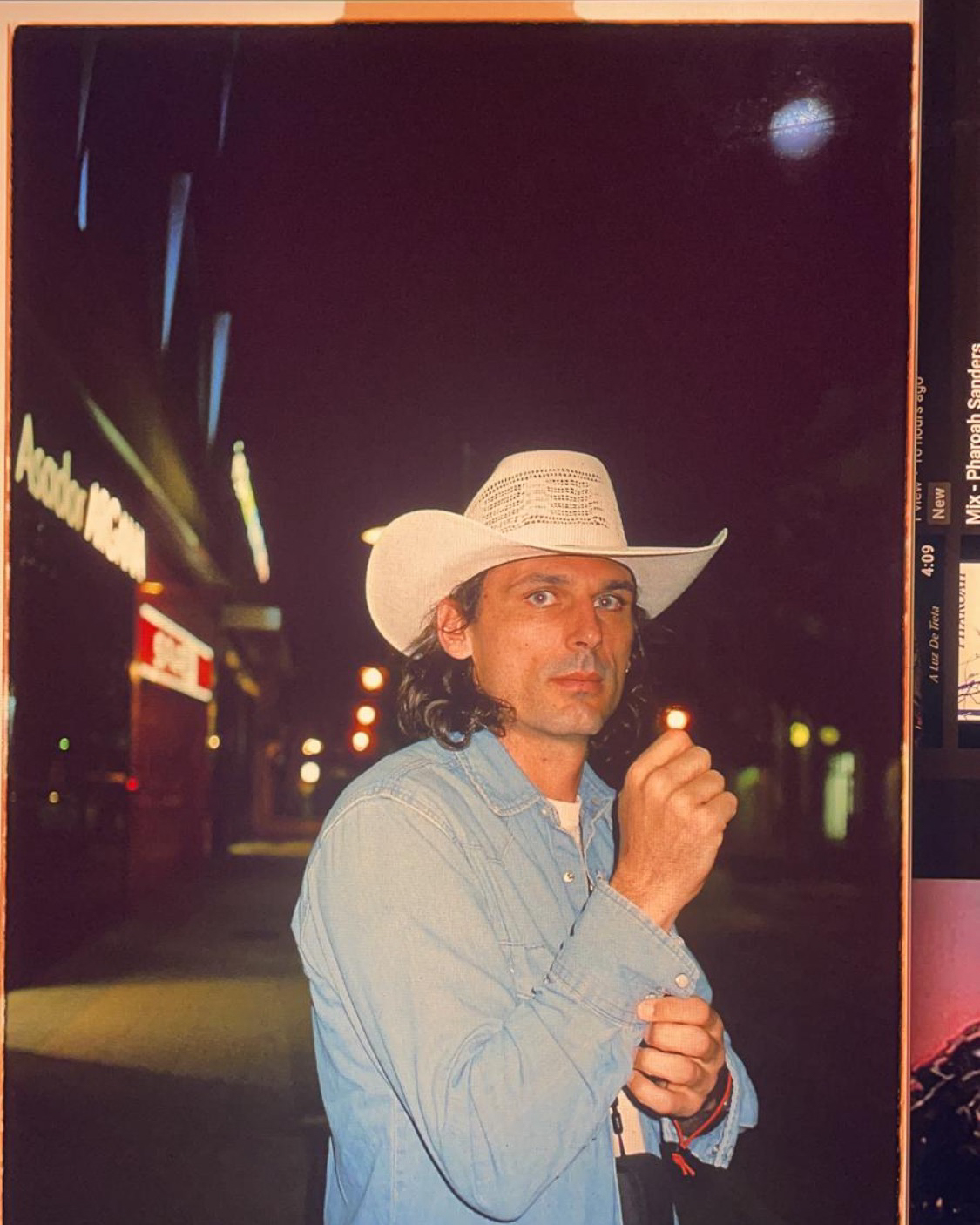

Taking the phone off its cradle, our call continues as Gus reaches across to the passenger seat and picks up a pristine white stetson that he places squarely on his head—his Instagram bio leads with All hat, no cattle—with the camera following as he walks through an echoing series of empty corridors. And it’s during this brief interlude that I learn he no longer has Terry.

“He lives just outside of Fresno. My partner and I moved in together—we’re actually engaged—and she has a German Shepherd. And both being big dogs, they used to fight all the time and it got a little hectic. But Terry’s good; I call in to see him whenever I’m driving up to Lachy’s* place. He’s actually hit the jackpot living with a family on this huge ranch where he gets to stretch his legs.”

*Gus’ younger brother Lachlan Morton

So it’s clear that domestic arrangements have changed somewhat—including a move of a few miles from Echo Park to Highland Park—with the remainder of Gus’ news centering around being busy. Very busy.

“There’s been some pretty big projects that I’ve been working on: Crit Dreams, The Divide, Great Southern Country. Add in some shorter content and all that means—until very recently—that I’ve not been riding my bike as much as I’d like.”

A response that is perhaps slightly ironic. Because it’s the bike and bike riding that prompted me to reach out after I spotted Gus, snapped standing at the roadside, wearing his familiar white stetson, in a photograph taken at last year’s TSP* race from Los Angeles to Las Vegas. But rather than the usual running relay where teams of three cross vast, often inhospitable distances; for the very first time TSP was being raced on bikes. But trying to dig a little deeper—researching the event prior to our call connecting—proved surprisingly challenging. Or perhaps intentional, going by the TSP tagline No spectators?

*The Speed Project

“That actually references the philosophy of TSP founder Nils Arend,” explains Gus. “Going back 13 or so years to when they ran it for the first time. This idea of No spectators meaning that everyone’s a participant. Whether you’re watching from the roadside, crewing a team, or taking a pull in the relay; everyone is helping out in some way or other. And I love that as a concept because what it’s basically saying is that we’re all part of it. In the sense that you take Lachy’s ride around Australia which we filmed. Yes, he rode the bike, but without the support of the crew, there’s no way he would have set the record.”

Click image to open gallery

As it turns out, Gus’ involvement in TSP originated through a good friend of his, the director and photographer Emily Maye. Working on a project that featured TSP back when Gus had first moved to LA, when they caught up a little while later, Emily started talking about this crazy relay race covering vast distances where people switch on the fly.

“It just sounded so wild,” Gus remembers, “and straight away it got me thinking about what it would look like as a bike race. And then we’re a couple of days from finishing up filming The Divide and I get this text message from a number my phone doesn’t recognise. Turns out it was Nils who’d got my contact details from Emily. He was asking whether I wanted to shoot TSP in Chile where the teams would run across the Atacama Desert. So long story short, we head out to Chile where Nils and I very quickly become fast friends—similar personalities and outlook on life—and he was also wondering what a bike version would look like.”

So the idea obviously had legs, I suggest?

“Straight away, in typical Nils fashion, he said let’s do it. And he was dead serious which is why, three months later, we did fucking do it. I’d never organised anything like that before but basically you figure out where you want to start and where you want to finish and off you go.”

Without a fixed route for everyone to follow, the teams were given a series of checkpoints and then had to decide for themselves how to reach them.

“The checkpoint locations were only released ten hours before the race got underway, so the whole event had an element of make-it-up-as-you-go. Which also meant that each team could turn the event into whatever they wanted it to be. Which, in turn, plays into the No rules tagline. They got to set their own boundaries, be creative in the space they were given, which allowed so many different people, from so many different backgrounds, to not only get something out of the race but also be a part of this bigger community. In a sense, everyone had enough freedom to create their very own version of TSP.”

Click image to open gallery

That’s assuming, I can’t help wondering, whether anyone even knew there was a race happening?

“The way that it works—for both the running and cycling events—is by word of mouth. So that might involve asking someone who’s already done the event and they’ll point you in the right direction. Which is kind of funny because last year it was the first time we’d done a cycling version of TSP. But someone hears a rumour and they tell someone else and they’re interested and it kind of goes from there. And that’s one hundred percent intentional because we want this experience to evolve through the participants themselves. So as organisers—if that specific term even applies—we want to be as hands-off as possible in that regard and ensure that we don’t force our own point of view on what it should look like. We feel it’s important to allow the space to develop however people want it to.”

So it’s a race with teams competing over a set distance but on routes they figure out for themselves and without a podium to celebrate placings? That’s some kind of a crazy mash-up, I suggest.

“We don’t award any prizes but human beings are hardwired—and I’m speaking in extreme generalities—to be competitive to some degree. A character trait that I don’t see a problem in acknowledging unless it involves a win-at-all-cost attitude whereby you lose sight of why you initially embarked on this or that experience. So my own buy-in to this event was that it’s fine to be competitive but I don’t want people to feel they have to be. Which then plays into not wanting a prize to be the motivation for lining up at the start.”

Considering it’s very difficult to spot who placed where in the finish line photographs—seemingly everyone is smiling and hugging each other—this offers a marked contrast to World Tour racing where the winning rider crosses the line with arms held aloft and second place is commonly pictured slamming their bars in frustration at wasting all that effort.

“In my mind,” responds Gus, “I imagine how cool an event would be where first and second race each other as hard as they can but when they get to the end, they’re excited to learn about each other’s race and how it all went down. As opposed to winning and it’s hell yeah, that’s what I came for, see ya later.”

Because sharing stories is the prize?

“Exactly. The prize is what you make of it. Because Nils and the team behind TSP have built this insane sense of community. Which means that you might have teams lining up in Santa Monica with wildly differing aims and objectives. And you know what? It’s infectious and it’s cool and that’s coming from someone who generally likes to keep to himself and do his own thing.”

Click image to open gallery

Pictured as he was on the roadside during last year’s running of the event, I’m curious as to exactly what role Gus played?

“I guess you could say I was bringing my knowledge of bikes and cycling to whoever needed it.”

You were an available resource?

“Yeah, that’s about the size of it. Just helping out.”

And as for taking part if there’s a follow-up event?

“I would love to and that’s saying something in itself. Because when last year’s TSP CYC took place, I hadn’t properly ridden a bike for years and was the least physically healthy I’d been in a long time. But over the past six months I’ve really been riding a lot. At least in frequency if not in distance. And I guess I need to take part to truly understand what everyone is talking about.”

Including the afterparty, I prompt. Which going by the running editions, are known to be rather legendary?

“For our event last year, the afterparty was probably best summed up as a lot of conversations, a lot of new friends, a lot of quick bonds formed by having barriers that were previously in place being removed due to the nature of the event. Everyone connecting over how crazy it was to ride your bike for hundreds of miles, non-stop, across pretty gruelling terrain and figuring out this weird journey on the fly.”

There’s an excited edge to Gus’ voice as he paints this picture of a disparate group of people all sharing their own, individual stories from the road. Stories that—going by TSPNo rules tagline—might reference some rule breaking?

“There were no rules so I guess not,” fires back Gus with a laugh.

But it’s all so achingly cool, I tease. And possibly there’s a perception that TSP is akin to a private member’s club where you post images and videos tagged with IYKYK?

“I do get that. Because it’s not like there’s a website where you click a link, pay a fee and you’re registered. But like I said before, maybe it’s as simple as just reaching out to someone who’s done it and asking how they ended up taking part. And at least that’s now a little bit easier because there has actually been one. So yes, there’s a step to participating but maybe that step isn’t as big a hurdle as people think it is.”

And hurdles can be a good thing, I counter. Because in life most things that take some effort, some investment, usually give back the most?

Click image to open gallery

“I’m not going to tell you that this is categorically the best way to put on an event. In my mind—or at least the way I see things at the moment—there is no better, only different. And that’s also what I love about TSP. Because it’s not for everybody and nor should it be.”

Gus pauses here for a second as he pulls together his train of thoughts before continuing.

“Before it came along, there wasn’t really anything like it. So maybe it does cater for a certain type of person but you could argue how they didn’t have anything before and it’s filling another little piece in the puzzle of human expression and it is what it is. In the same way that I’m not mad at whoever puts on Unbound; an event I have zero compulsion to race. I’m not, fuck those guys for putting on that fucking event. I don’t give a shit. As long as you’re not hurting anybody, do whatever you want.”

As to whether they’ll be another TSP CYC later this year, Gus is—in this particular instance—without an answer.

“We don’t have any dates yet. But I think it will happen.”

So watch this space?

“I don’t drive the ship or anything. I’m just a fan and possible future participant.”

With our time together drawing to a close, I can’t resist winding the clock back a few years to a conversation we had in Girona where we touched on Gus’ groundbreaking partnership with Rapha and, in particular, his lead role in the brand’s promotional short Riding is the answer. Which, in itself, begs the question whether that statement still holds true?

“You know, I’ve not thought about all that for so long. Because what’s changed is that I don’t need to race anymore, I don’t need to go on anyone else’s adventure. I don’t need to be posted on anyone’s fucking Instagram. I’ve become more private which means that now my riding is just for me. But, within that definition, I guess you could say it’s still the answer.”

There’s a hesitancy in Gus’ voice that suggests he’s not quite finished.

“Maybe it’s the question that is different. Because previously cycling was the hurly-burly, the shark bait that I used to attract the characters that interested me. So you could argue it stopped being the question in 2017 when I got done with Outskirts. And maybe it’s now become an altogether different thing.”

Angus Morton / thatisgus.com / Thereabouts / The Speed Project

All photography with kind permission of Paulin Rodenstock:

“When I was asked if I wanted to come along as the photographer on a bike race in America—where no one really knew what to expect—that was one of those moments in life when I just felt…free. And I can’t really describe it any better than that.

Because descriptions are not always simple and straightforward. Which is perhaps why I can’t easily explain what photography means to me. It kind of snuck up on me; little by little. And maybe that’s why I enjoy it so much—because I never set out with any specific goals. I just started doing it because I liked it.

For almost a year now, I’ve been a full-time professional photographer. And my favourite photos are often the ones taken in secret—the ones where people later look at them and say, “Crazy, I didn’t even notice you were taking my picture.”

Of course, over time, your technique develops. You understand the dos and the don’ts. But very often, the images form spontaneously in my head—or even momentarily as I press the shutter.

I like photographing in colour, but I love black and white even more. Colour is something familiar but black and white adds a certain something that you don’t see every day. It draws attention to things you might otherwise overlook.

TSP last year was probably one of the most incredible things I’ve ever photographed and experienced. And even though, as the media team, we spent most of the time in the car, so much happened that—almost a year later—I still look at the photos and can’t quite believe what I’m seeing in my own pictures.”

With grateful thanks to RAD COMM / Jakob Flanderka / Felix Hartas