I’m told it’s downstairs in the basement showroom of the Condor bike shop. And sure enough, when I descend past the window that fronts onto the busy London thoroughfare of Gray’s Inn Road, I find a matte black bike with deep section tubular race wheels waiting its turn with the Condor mechanics. Apart from a pink stripe that paints a line down the centre of the saddle to reappear on the flattened profile of the aero bars, it looks fairly understated. Obviously built to go fast with brakes hidden away in the front forks and tricked out with an expensive groupset, what makes this bike particularly interesting is that it was designed to race at the Hillingdon Circuit by its owner; Dominique Gabellini. And that’s just Hillingdon.

Later in the morning, when we meet over coffee in the ground floor cafe at Rapha HQ, Dominique sets the design considerations of this particular bike in some context: ‘For Hillingdon, I knew I needed a very aerodynamic frame so I went to see Condor and said I wanted this, this and this and they spoke to the engineers in Milan and the discussions went back and forth from there.’

Perhaps unusual for an individual to have such easy access to a design team for what is, in effect, a one-off build? But this simply goes to illustrate the breadth of the relationships Dominique has built through an amateur racing career that began in the south of France as a teenager before a return to competition in and around London at the age of 45.

Although playing table tennis to a good standard in his early teens, Dominique grew bored and took up cycling; winning races by the time he’d turned 17 before signing with an amateur team. 3 years later he’d decided to quit and go to university; a decision he levels at the mental challenge of stepping up to an elite level of racing. ‘I’d been told when I was younger that I’d be very good and then, on the first day of my first stage race, I was dropped. There was an echelon and I didn’t have the experience, the understanding of what was happening. I was always at the back and then out of the door.’

‘And this was difficult,’ Dominique continues, ‘because I’d been winning races – winning quite easily – but when I moved up to stage racing it was beyond my standard. It was very hard and, mentally, I wasn’t prepared for it. I was too inexperienced and I’d started racing too late.’

Admitting that these are not particularly fond memories, the contrast to the time he spent racing prior to signing his amateur contract is all the more intriguing. ‘I was part of a group of riders that we called a mafia. We did all the one day races and made a good living from the prize money.’

Describing how he travelled by car between provincial French towns, his voice and gestures animate as he recollects contesting one race after another. ‘If it was a nocturne we’d usually start at eight in the evening before driving to the next town in the morning. And we made so much money. Enough that I could buy a car – a Fiat 127 – at the end of the season. And alongside the prize money you’d win a leg of lamb or a case of wine which we would sell to the hotel.’

‘But we had to work hard for the wins,’ he relates with a smile. ‘When you had two or three mafias turning up at the same race, it was a fight. The race was so fast. And it’s important to remember that for my team-mates – who were much older than me – it was their job. They cut wood in the winter and raced their bikes in the summer.’

Contrasting these obviously good times with his later experience of stage racing, with maturity Dominique has since placed this in some context. ‘I never, ever, finished in the peloton in any of the stage races I contested. And looking back, do you realise how depressing that must have been for a 19 year old? Sometimes I was finishing 20 minutes after the main field. The last rider to be massaged, the others had finished their dinner by the time I sat down. That was my life. And I was riding with guys in their late twenties, early thirties, who’d all left school at 14 because they went into cycling. But that hadn’t been my path. I had a baccalaureate and the conversations we did share were limited as we had so little in common.’

Needing time to reflect on future plans, Dominique attached a rack and panniers to his racing bike and set off for Italy to see his parents. On his return he rode and won one last race before climbing off his bike and informing his father that he was continuing his education and enrolling in university. He wouldn’t compete again for another 24 years.

After graduating with a degree in International Relations, Dominique moved to the UK to study English before settling in London and establishing his own language school. ‘I was working in excess of 50 hours a week – Saturdays and Sundays – but I enjoyed it because I was creating something that didn’t really exist at that time.’

Referring to a business model that had his employees teaching in their clients’ homes or offices, at the time this proved a groundbreaking innovation. ‘We didn’t have any spare money for premises,’ he adds rather ruefully. ‘Everyone does it now but back then it was a novelty.’

It was his cruciate ligament, injured whilst playing tennis, that led to his doctor suggesting he start riding a bike to help build the muscle. As his office was located 10 minutes from the Condor shop, he called in one morning to purchase a bike. ‘When I mentioned I used to race,’ he recalls, ‘I could tell from their reaction that they didn’t believe me.’ Nonetheless Dominique started to train; riding laps of Regent’s Park where he made some friends who encouraged him to consider a return to competition. ‘They took me to a race and I won. Two years later, when I was 47, I won 30 races before realising that when you reach a certain level and you race on your own it gets very hard. So I approached some other people and asked them to ride with me and this became the foundation for the first Condor team.’

Speaking over the phone to Grant Young, son of Condor’s founder Monty Young, it’s clear that the seeds for a close friendship were immediately sown when Dominique first walked in off the street to purchase a bike. ‘We bonded the first time we met,’ confirms Grant, ‘and from day one he was a very loyal customer. A relationship that became, over time, more of an ambassador role and led to us establishing a small race team. We were happy to offer our support as it worked really well and everyone wanted to race with him.’

And it was also around this time that Dominique first met Rapha’s founder and CEO Simon Mottram and learnt of his plan to set up a new company that would retail high quality, carefully considered cycling clothing. As Dominique recalls: ‘He was just starting the brand and asked me if I’d model for them. We went down to the south of France for the shoot and for the next four, five years I continued in that role. And, looking back, those images were seen as being quite iconic in the way they were art directed and subsequently used in marketing campaigns.’

With this relationship now firmly established, when the Rapha Cycling Club was founded in 2015 it was a natural step that Dominique take on the role of ride ambassador; leading groups of members on rides into Hertfordshire and the Chiltern Hills or seeking out lesser known trails and pathways on his cyclocross bike. A role that compliments his continued love of racing as it’s clear that Dominique still has the same passion for competition that first prompted him to take up the sport as a teenager. ‘I perform best in crits,’ he confirms. ‘I like the adrenalin, the speed.’

Excited by the current crop of cycling talent and encouraged that women’s cycling is gaining more media attention, at 61 years old Dominique recognises that the way he competes is, by necessity, different to his earlier racing style. ‘Now that I’m older I know I can’t make the break in an elite field. I stay in the peloton, making sure I’m in the first fifteen and, if there’s a sprint, I try my luck from there.’ With a trim figure honed from weekly 5 hour cyclocross sessions, he continues: ‘In a race you’re constantly weighing up the field. You know who to follow and who won’t have the legs. Sometimes you make the wrong decision – I often make the wrong decision – but that’s racing.’

As our time together is drawing to a close – the cafe is beginning to fill as lunchtime approaches – I ask whether Dominique has any regrets in a life, appreciably in two distinct phases, spent racing? At this, he smiles before answering. ‘I enjoyed many good times but I don’t regret going to university. I saw the doping. Knew of the ‘understanding’ certain teams had with race organisers. And there were no miracles back then. You trained and worked hard. The people that were so far above us; they had something else.’

Still racing 2 or 3 times a week in London – riding to the circuit, competing and then riding home – perhaps rather typically he describes how his mood alters if he can’t get out on his bike. ‘I become unbearable. My whole life revolves around cycling and my roles with Rapha and Condor.’ A relationship that Simon Mottram is quick to acknowledge when reflecting on Dominique’s involvement since the launch of the brand in 2004. ‘Dominique has been central to the whole story of Rapha and our success to date. He’s been a model, product consultant, ambassador and connector for the brand. But more than that, he’s been a riding companion, friend and inspiration to me for thirteen years.’

And judging by the number of times our conversation has paused as friends stop by the table to greet Dominique and share a few words, it’s clear to the extent he’s held in such affection. ‘I know them all,’ he remarks as his gaze takes in the various groups of people sitting at neighbouring tables. ‘They are a family to me.’

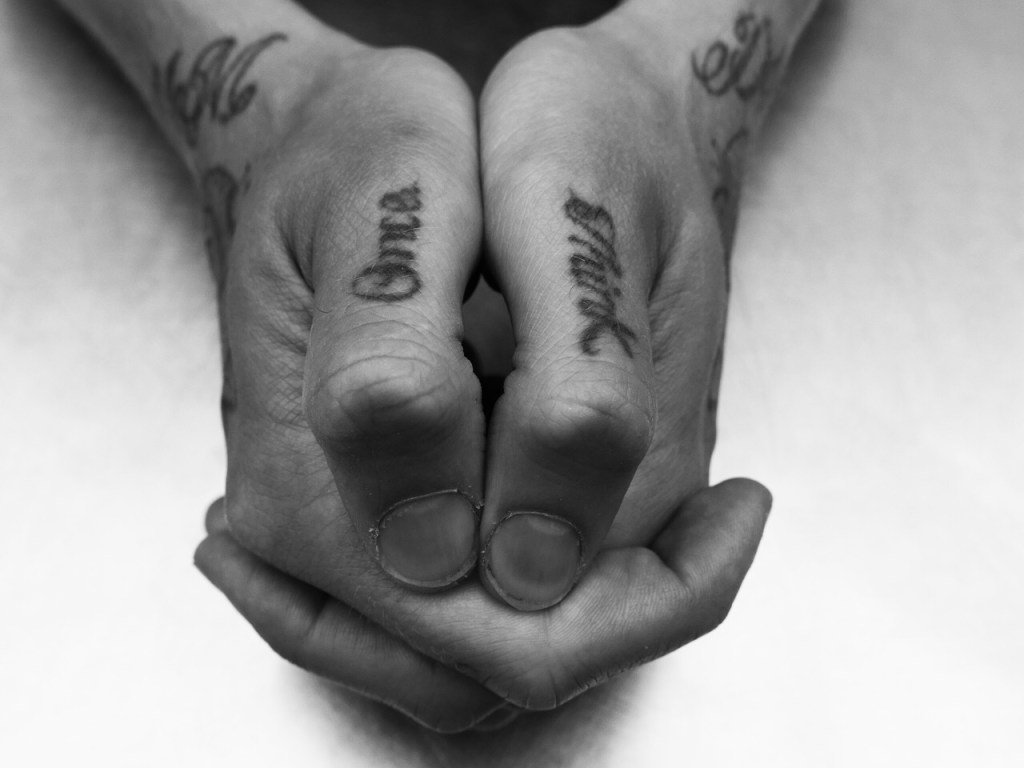

All images by kind permission of Rapha